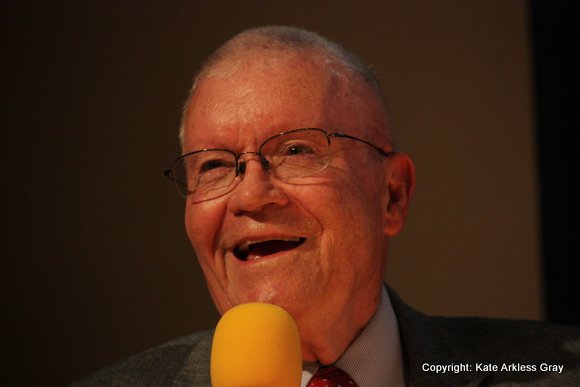

You’ve seen the film, you know the dramatic story, but meeting one of the members of the ill-fated Apollo 13 mission is something else. Ken Willoughby and the Space Lectures team secured Apollo 13 Lunar Module Pilot Fred Haise as their guest of honour in Pontefract for the final weekend of October. We all came away knowing something new – though not perhaps what we had expected…

“My name is Fred Haise, I’m a NASA astronaut” begins Haise, “I flew Apollo 13 a while back”.

“My name is Fred Haise, I’m a NASA astronaut” begins Haise, “I flew Apollo 13 a while back”.

Thus begins my chat with the understated Fred Haise. “I wanted to be a journalist” he tells me, “I studied journalism for two years at junior college and freelanced for AP – they paid 75 cents a line”.

It was the outbreak of the Korean War that changed his course as he joined the naval aviation cadet programme. “I’d not been interested in flying, I’d never flown, but I loved flying” he says, “that made a right turn in my career”.

There’s something very matter of fact about the way he describes joining the astronaut corps. “I’d been working at NASA before, so for me it was just another transfer from one NASA centre to another one”.

“I didn’t think of myself as a particularly renown person at the time, I was just a test pilot” he says.

There’s that word again “just”. It’s a word he seems to use a lot when talking about himself. I can’t tell whether that’s because he’s uncomfortable with the level of recognition and awe he now commands, or that it’s a reflection of his view that he was “just” a test pilot, getting the job done.

That’s not to say he’s blasé about it, “I feel very fortunate to have stumbled into this line of work” he says.

A few minutes into his lecture at the Carlton Community High School, Haise mutters that immortal phrase: “We’ve had a problem”. This time however, it’s just an issue with the microphone he’s using to deliver his talk – we share a moment of laughter as they disentangle him from the wires of the headset and give him a hand-held mic instead.

A few minutes into his lecture at the Carlton Community High School, Haise mutters that immortal phrase: “We’ve had a problem”. This time however, it’s just an issue with the microphone he’s using to deliver his talk – we share a moment of laughter as they disentangle him from the wires of the headset and give him a hand-held mic instead.

“There was no book for this set of problems” says Haise, referring to the multiple failures caused by the oxygen tank explosion on Apollo 13. Despite many hours training in the simulators at both Johnson and Kennedy Space Centres, the escalating string of issues they had to deal with was something new.

In fact, one of the reasons they’d not planned for it was that the problem was so serious an issue that crew were lucky to have survived it at all.

“We kinda gave them a problem” he says, “we were still sitting there breathing”.

The mission control team had their work cut out. Although the initial aim of the mission, a Moon landing at Fra Mauro, was lost, the crew were not – and that meant they had to work round the clock to return them safely to the Earth.

It was not like a car swerving off the road though, says Haise, in fact it took Mission Control 18 minutes to come to the same conclusion that the crew had come to, that the oxygen tank was lost. “Sy Liebergot got a lot of heat for that” he says, “for 18 minutes they thought it was an instrumentation problem”.

The crew had been filming for a TV show two days into the mission, finding things to show people that the other missions hadn’t already covered, giving a little tour of the vehicle and enjoying the effects of microgravity – “it’s kinda euphoric” he says.

TV transmission from the Apollo 13 crew moments before the accident that crippled the mission. Fred Haise can be seen on the large screen at the upper right.

It was at the end of the filming that they had the problem. “It ended up being a very long day” he says earnestly.

“Initially I was still in the landing craft, putting away stuff” he explains. “By the time I drifted up the tunnel to the right seat – that had all the electrics – all three meters were down at the bottom for tank two”.

“I just had a sick feeling in my stomach. I knew that we had lost the landing. Without referencing mission rules or the books I knew that was an abort, to lose one of the tanks.”

Haise had trained as back-up for both Apollo 8 and Apollo 11, but this was his first flight. “Here I had my chance, and it was gone in an instant”

This last line, delivered with an almost imperceptible tinge of sadness, a little quieter than the others, is the closest I feel I’ll get to the truth of the disappointment. Haise is a military pilot, a test pilot, a “stiff upper lip think of the mission” pilot. There’s not room for emotion when you’re thinking of the next thing that could kill you, and while he talks at length about the technical details, he doesn’t give much away about the emotion behind the experience.

This last line, delivered with an almost imperceptible tinge of sadness, a little quieter than the others, is the closest I feel I’ll get to the truth of the disappointment. Haise is a military pilot, a test pilot, a “stiff upper lip think of the mission” pilot. There’s not room for emotion when you’re thinking of the next thing that could kill you, and while he talks at length about the technical details, he doesn’t give much away about the emotion behind the experience.

I wonder if he’ll say more, but we’re back onto the timeline of what happened, how it panned out and who knew what, when.

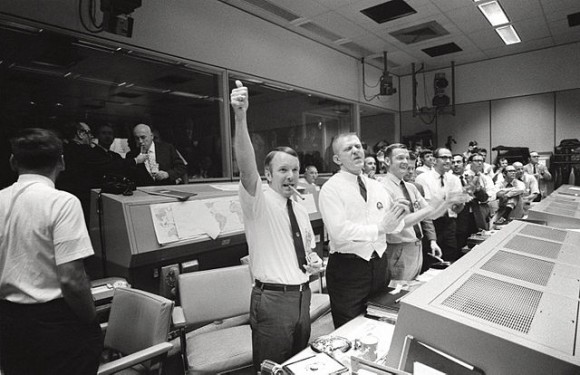

Haise is keen to point out the sheer number of people who worked the problem and got the crew safely home. “One of my main complaints to Ron Howard about the film (Apollo 13) was that it didn’t show the number of people involved” he says, though he admits Howard pointed out he had neither the budget for so many actors, nor the time to introduce them all as characters in his blockbuster film. Fair point.

“A few years ago I listened to the back room loops” says Haise, referring to recordings not of the space to ground communications, but those containing the discussions in the “back rooms” – the rooms of experts that supported those people in the main Mission Control centre.

“We were desperately trying to isolate the leak in the second oxygen tank” he explains, “we would have aborted even without that, but it wouldn’t have been as bad as it was”.

Listening to the tapes, decades after the incident itself, he describes hearing the voices of people he knew – hearing from the inflection in their voices that they knew they’d lost it, and they were losing hope. A new Mission Control team came on and they realised they had to shutdown the command module, and fast. “We were eating into our entry batteries”.

There was a change in the voices, some hope, but now they had a new problem to deal with. The command module was never meant to be shutdown during flight so there was no manual for the procedure. Despite that the team worked out what to do and they worked through the shutdown sequence and managed to do it safely.

“When I listened to the tapes, it really made me want to applaud” he says, with obvious admiration for the commitment and skill of those involved.

Commander Jim Lovell tasked Haise with calculating the consumables required, assuming a return time of around 150 hours. Haise recalls that they were running out of water, but he thought that they were okay on electrical power, and plenty okay on oxygen – especially with the two suit tanks that were no longer required for Moon walks. He didn’t think of carbon dioxide as a consumable and missed that from the calculations – though of course it was the build up of carbon dioxide that caused another big problem for them, requiring them to create a makeshift CO2 scrubber.

Commander Jim Lovell tasked Haise with calculating the consumables required, assuming a return time of around 150 hours. Haise recalls that they were running out of water, but he thought that they were okay on electrical power, and plenty okay on oxygen – especially with the two suit tanks that were no longer required for Moon walks. He didn’t think of carbon dioxide as a consumable and missed that from the calculations – though of course it was the build up of carbon dioxide that caused another big problem for them, requiring them to create a makeshift CO2 scrubber.

“It went real cold so we stayed in the LM(Lunar Module)” says Haise, “we didn’t go into the ‘icebox upstairs’ as we called it”, talking of the shutdown command module.

The crew were no longer able to heat their food and soon gave up on trying to eat anything powdered. “We ate cookie cubes, bread cubes and peanuts from a little larder of snacks” he explains.

Cooling vapour being released from the lander (not usually present when returning from the Moon) had pushed them slightly off course – enough that the craft could have “bounced” off the atmosphere and been lost forever. They had to correct for this, without the computer and without being navigate using the stars since there was still too much debris glistening around them. Instead they used the Earth’s terminator – the line where the light of day and shadow of night meet – for guidance.

“We did two short burns, one of 18 seconds, one of 21 seconds. One with the descent engine and the other with the four RCS (Reaction Control System) engines” says Haise, explaining that unlike the way the film presents it, they didn’t swing around all over the place – that was just put in for dramatic effect.

“We did not move more than one degree in any deviation in any axis” he states firmly. Jim Lovell controlled the yaw of the spacecraft, while Haise controlled their pitch. He lightens his tone to mention “the biggest deviation was in Jim’s axis”, adding a wry smile.

Despite all the issues, not only did the crew get back safely, but their splashdown was one of the most accurate of the whole Apollo programme. “Only Apollo 10 did better”.

It’s an impressive feat, and the crew’s safe return deserved some celebration, but unlike other missions there was no splashdown party when the crew landed. Those in Mission Control were too tired, some of them having never left once they were called in, choosing instead to lie down in corridors to nap when they knew they needed to. They celebrated by getting some sleep.

Haise tells us the Apollo 13 crew are unique in that they were allowed to go to their own splashdown party, which was held two weeks later. What a party that must have been!

He survived Apollo 13, but sadly the next mission he was slated for, Apollo 19, did not survive financial cuts. His chance at the Moon really had been lost in an instant.

Haise is asked about his role as CapCom for Apollo 14′s Moonwalk – which had inherited Apollo 13′s landing site – was that bittersweet for him?

“Bittersweet?” he says before a pause, “Every time someone landed on the Moon it was bittersweet – not just 14.”

But he’s lucky to be alive – and Apollo 13 was not his only narrow escape. Continuing with flying he had an engine fail at around 300ft on the set of the Pearl Harbour film “Tora! Tora! Tora!”. Attempting to land in what he thought was a dirt field, he found the start of a housing project, filled with ditches. Having caught a wheel in a ditch, he was in trouble. Trouble that left him with second degree burns over 65% of his body.

After months of treatment, and many more to get back to flight status, Haise was ready to take to the skies again. In 1976 he joined one of two duos tasked with carrying out the approach and landing tests for the latest space vehicle, the space shuttle.

Sitting up in the shuttle cockpit atop a 747 plane that took them up to around 30,000ft for the test was “like a magic carpet” he says. “You couldn’t see the 747 at all.”

Haise takes a detour from speaking of his direct experiences at this point. “Apollo was a very unique programme” he says. “Lots of things all lined up at the right time to allow it to be properly supported and funded.”

“But why did it happen then and not since?”, he asks. His answer comes in three parts – firstly, there was a threat. The Soviets, with Sputnik and Gagarin, made the US feel threatened.

Secondly, John F Kennedy wanted a way to declare the technological capability of the US. Various options were suggested, but the Apollo programme happened to tick the right boxes. “I don’t think, personally, that he was a space fan” says Haise.

Finally, for something like Apollo to become reality, there cannot be something else drawing on your national budget, like a war.

“You can dream about doing something, but you better have the technology to pull it off” he says.

Haise shares his views on the way the space shuttle programme was squeezed and the issues that caused. “Content got taken out of the programme” he says, “They cut the second Enterprise (test vehicle) and moved OV-99 from being a test vehicle to a flight vehicle”. (This orbiter later became more commonly known as Challenger.)

Haise shares his views on the way the space shuttle programme was squeezed and the issues that caused. “Content got taken out of the programme” he says, “They cut the second Enterprise (test vehicle) and moved OV-99 from being a test vehicle to a flight vehicle”. (This orbiter later became more commonly known as Challenger.)

The whole shuttle programme was delayed, with the first orbital launch coming two years after its original scheduled date. This is one of the reasons Haise didn’t make a return to space on the shuttle.

Haise also mentions the “worrisome” nature of a change in administration from Nixon to Carter. Carter cancelled the B1 bomber project just at the time they were conducting the approach and landing tests for the shuttle, “it was pretty obvious that space was not in his top ten priorities” he says.

“That morning when we climbed into Enterprise there were Polaroids stuck on the steps at the top” says Haise. The photos showed their colleagues dressed in blue suits (flight suits), wearing hats and masks, pretending to be Haise and his crewmate

Gordon Fullerton. They were sat posing on a street sweeper with the message: “If you foul this up, this will be your next job!”, written on the photos.

It may have just been a prank, but it reflected everyone’s worst fears. Had they crashed Enterprise it would have set the programme back by at least two years, says Haise. Thankfully that didn’t happen and thirty years of shuttle flights ensued.

“I just feel very fortunate with my total career” says Haise.

“Magically, luckily, I got into flying. I was going to be a journalist – like Kate here, making notes” he says picking me out of the crowd and causing me to feel simultaneously self-conscious, and proud at having been name-checked by an Apollo astronaut.

“Magically, luckily, I got into flying. I was going to be a journalist – like Kate here, making notes” he says picking me out of the crowd and causing me to feel simultaneously self-conscious, and proud at having been name-checked by an Apollo astronaut.

Haise closes his talk by saying “I arrived at the right time, with the right experience and the right background for Apollo”.

“Today they are people with the same credentials, but no programme to go into” he adds, slightly ruefully. “I feel very lucky to have had the chance”.

The room fills with applause and he is given a standing ovation. At 81 later this month, Haise is in fine form, and despite talking late into the evening the night before, he patiently signs autographs without a flicker of tiredness.

I feel very lucky to have met him. Journalism’s loss was definitely NASA’s gain.

It’s been a tough week for commercial spaceflight. We know spaceflight is hard, but two stark reminders so close together really bring the message home.

Before I realised that space was “real”, before I met someone who actually worked for NASA, these stories might have caught my eye in the paper, made me gasp at the images, then floated away from my consciousness somewhat. Even when I went to see my first rocket launch, which was meant to be a shuttle, I was there for the excitement, the spectacle, the sight, sound, experience of it all. To see a mighty rocket lift off toward space.

I didn’t really think of the astronauts. I mean, they weren’t quite real, in the same way that NASA was distant and untouchable – like something from a film, astronauts were sort of like superheroes. Not quite real, so you didn’t have to worry about them, they were superhuman, untouchable, they exist like Father Christmas does… (We know he exists, but you’ll never actually meet him!) ![]()

But when I got to know an astronaut, and when I sat and watched as tonnes of rocket fuel were ignited beneath him on a rocket that blasted away from the confines of Earth, it was different. It wasn’t just a spectacular show – an amazing human achievement, an exciting thing to watch – it was terrifying. We say we know that spaceflight is hard, but then we act as though it isn’t. Astronauts aren’t scared, things are nominal, *another* successful launch etc. But when you know someone on top of a rocket, you’re keenly aware that this stuff is hard. Really hard. It is risky.

You remind yourself your friends have trained for years, that they are smart, prepared, that they understand the risks etc. You tell yourself it will be okay, but until you see them safely on orbit, or back on the ground, you are intensely aware that spaceflight is hard.

Busy editing some audio from the International Astronautical Congress, I was a few seconds late getting NASA TV to load so I could watch Orbital’s Cygnus launch on October 28th. When the feed finally loaded there was just fire everywhere. “That’s not good” I thought, immediately. You don’t want to see that much fire after a launch.

There was silence. And fire. This was bad.

I scrolled back through the tweets in my feed. It was spooky. The usual crowd getting excited about the countdown, sharing the livestream link with others, then “LIFTOFF!”, “Go #Orb3″, “Cleared the tower! :D”, followed by “Shit!”, “omg”, “oh crap”. Fifteen seconds into flight there was (in space speak) “an anomaly” – a catastrophic failure to you and me – and the range safety officer made the call to destroy the rocket to minimise further potential damage.

I sat listening to the livestream as the commentator struggled to keep sounding calm and find enough things to fill the airtime, giving what little information they had at regular intervals. But what was there really to say? The third launch of Orbital’s Cygnus craft had ended in a matter of seconds. Burning debris told the rest of the story.

We heard the comms loop as people were told to keep all their notes, data, anything that might help the investigation. Then there was the silence, nothing but the sound of the wind and the sight of the launch complex with fires burning all around.

I was in shock. I was used to coming online for a launch, chatting with fellow space fans from around the world, and watching as rockets lifted off in a blaze of glory.

Thankfully this wasn’t a crew launch. We had confirmation that staff at the launch site were safe. What was lost was the payload destined for the ISS, numerous satellites (including those from a friend’s company) and the work of hundreds, more likely thousands, of people.

Previously I would have felt no real connection to any of this, but having followed the progress of commercial companies delivering cargo to the ISS, and with friends at SpaceX, I felt a real sadness on behalf of all those trying so hard to make this work – to see all your hard work destroyed in a matter of seconds must be heartbreaking. Thank goodness no-one was hurt.

Spaceflight is hard, and when we get it right it’s something to be proud of, but we must never forget how hard it really is. My heart ached for the space family so many hopes, dreams and hours of work went up in smoke.

I went on holiday for a few days, disconnected from the internet a bit, had a break. Sitting ready to go out for some dinner my friend suddenly said “what? SpaceShipTwo has crashed”.

I felt a chill down my spine and went to find out more. Sure enough the news was just breaking on Twitter – not just a crash, but a fatal one at that. One pilot lost, the other’s status unknown.

Another commercial space disaster, this one including a loss of life, it felt too much.

I know people at Virgin Galactic. I’ve met one of their test pilots – was it him who had died? (Actually it turned out he was the survivor.) How must they all be feeling? The small space community at Mojave Air and Spaceport, were they all okay?

The commercial space sector, just learning to walk by itself, had taken another painful tumble.

Space is real. I think it’s hard for many people to grasp that unless they’ve been touched by it in some way – in the same way the realities of war are lost on those of us listening to reports on the news as we wake up. But it’s real to me these days and the past week has been tough.

Space is real. I think it’s hard for many people to grasp that unless they’ve been touched by it in some way – in the same way the realities of war are lost on those of us listening to reports on the news as we wake up. But it’s real to me these days and the past week has been tough.

I’m sending good wishes to the pilots’ families, all those at Virgin Galactic and Orbital, those involved in commercial space and to the whole space family. It is like a family, you may argue with traditional parents or squabble with rival siblings, but when it comes down to it, you want everyone to succeed.

There will be many months of investigation into both of these events, and it is right that serious questions are asked, lessons are learned and we move forward. For now though, I offer my support and best wishes to all those in the space family who need them. Space is hard, this has been a hard week, but we choose to do these things, not because they are easy…

I hope that those people involved can pick themselves up again, and continue the endeavour to reach for the stars. As rocketry pioneer Konstantin E. Tsiolkovsky once said, “Earth is the cradle of humanity, but one cannot remain in the cradle forever”. We’re just learning to walk, there will be other hurdles to overcome, but the only way we’ll do this is to do it together. My thoughts are with you all.

Opinion by .

The space generation – those us of born after the beginning of the space age – have our very own organisation – the Space Generation Advisory Council (SGAC). Set-up fifteen years ago, the SGAC brings together 18-35 year olds from around the globe to share ideas and opinions on the current global space arena. The SGAC works with the UN, especially the United Nations Committee on the Peaceful Uses of Outer Space (UN COPUOS) and has permanent observer status with COPUOS. A yearly congress is held alongside the International Aeronautical Congress, bringing discussions via email alive around the table.

I’m proud to have been voted in as one of two National Points of Contact to the SGAC for the UK earlier this year and I attended the Space Generation Congress in Toronto at the end of September.

To be honest, I wasn’t entirely clear what to expect, but any situation that brings me together with new people from around the world – especially those who share my love of space – is something to get excited about. Having packed a vast array of cool space tee-shirts to wear I was a little alarmed to find everyone else donning suits, but my suitcase thankfully contained a few extra outfits to cover me for the smarter attire.

This was no holiday camp! We started earlier and socialised until late. Lectures from prominent figures in the space industry, such as DLR head Jan Worner and NASA’s Director of Advanced Exploration Systems Division, Jason Crusan, were mixed with presentations from SGAC scholarship winners and working group time. The delegation of around 130 people, from almost 40 different countries, split into working groups covering Cubesat swarms, on-orbit servicing, earth observation for maritime services, entrepreneurship, and the ethics and policy of new space exploration strategies.

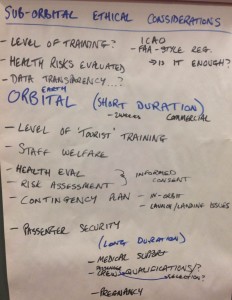

I joined the group looking at the ethics of future human space exploration and we spent our time discussing how a growing commercial space market might sit alongside governmental exploration strategies, and what ethical considerations needed to be taken into account.

While the rest of our working group exploring existing and future policy requirements, our sub-group quickly realised that it was not for our small group to decide on what was or was not ethical, but to consider creating a system that could evaluate individual missions. Taking our lead from the ethical review boards needed for medical research, we favoured a path where an international ethics review board is created to evaluate the mission profiles and preparations from both government and private missions.

Since even the term “exploration” could be contentious, we divided different elements of human spaceflight into categories, and explored what issues may need to be considered for each one. The different categories included sub-orbital flight (which we decided was more likely to fall under general aviation control/policy in future), short-term low-Earth orbit flights, long-duration low-Earth orbit missions, beyond low-Earth orbit, and one-way missions.

Since even the term “exploration” could be contentious, we divided different elements of human spaceflight into categories, and explored what issues may need to be considered for each one. The different categories included sub-orbital flight (which we decided was more likely to fall under general aviation control/policy in future), short-term low-Earth orbit flights, long-duration low-Earth orbit missions, beyond low-Earth orbit, and one-way missions.

The type of issues that we recommend bodies considering embarking on human exploration missions should consider included evaluation of health risks, informed consent for passengers/crew, contingency plans, medical support, and what to do in the case of a crew death. There would also need to be consideration of existing policies on planetary protection, utilisation and exploitation in space, and astronaut rescue obligations.

Our suggestion was that an independent review board be set up to evaluate the case for each mission profile that was to be launched, to ensure that there was some oversight on ethical issues.

There was some disagreement however about whether ethics board approval should be made a requirement, or whether it would serve as useful information for a launching state when they decide on whether to grant a licence for the launch.

We shall continue these conversations and write them up into a report that may be presented at the UN. If you have some thoughts on this topic we’d love to hear them – this is only the tip of the iceberg of a fascinating, and in my mind at least, important topic.

You can find out more about the different SGAC Project Groups, which are active throughout the year by clicking on the Project Group Page or by getting in touch with your national point of contact.

Events by .

A large bull fills the screen, then there’s a bucking bronco – not the sort you see at events, but a shot of a live bucking bull at a rodeo – its rider clinging on for dear life. Not the obvious first shots for a film about the last man to walk on the Moon; my attention is caught and my interest is piqued. Either the filmmakers have missed the point, or they’re doing something clever and they’re getting something very right.

The camera picks out a face in the crowd. Crisply in focus, you can tell instantly that this man has a story to tell. It’s our hero, Gene Cernan, white-haired and focused. The cinematography is excellent.

Back to the bull riders, twisting, turning, being thrown this way and that – and then the masterstroke, footage of the centrifuges that the Apollo astronauts were trained in – the spinning metal hulks that put them through their paces and tested them to the limits, just like the bull riders are tested to theirs.

They’ve got it right. I settle in to watch The Last Man on the Moon with renewed excitement.

The Last Man on the Moon -Trailer from Mark Stewart Productions on Vimeo.

I’d been kindly invited to a special preview of the film with the crew who put it together. In a small screening room at Dolby in London, we sat and watched the final cut. It was my first time seeing the film and the same was true for some of the crew who’d each worked on individual elements, from filming and editing, to digging through archive footage or creating props for some of the recreated scenes. It was a pleasure to be among them.

You might be expecting the film to concentrate on those famous final footsteps, and the emotion surrounding them, but in fact it’s only as the credits roll that you hear Cernan’s last words on the lunar surface “we leave as we came and, God willing, as we shall return, with peace and hope for all mankind. God speed the crew of Apollo 17”.

This film is much more about what led to that moment, as told in Cernan’s own words, archive footage and by the people who were with him as his journey unfolded. It’s done with sensitivity – without shying away from some of the hard truths like the loss of Elliott See and Charles Bassett, the original crew for Gemini 9 who died in a T-38 jet crash just months before their spaceflight. The archive footage of the charred remains of their plane being lifted onto a lorry is not something I’ll soon forget, and yet this awful event was accelerated Cernan’s first trip into space.

The beginning of the Apollo programme was not without tragedy either. The film movingly shows the effect of the Apollo 1 fire that killed Grissom, White and Chaffee, had on their colleagues and loved ones personally, and on the space programme.

I defy anyone to watch Martha Chaffee talk about the loss of her husband without at least a lump in their throat if not a tear in their eye.

Cernan admits that he neglected his family duties in his narrow-minded pursuit of his astronaut dreams. It’s a bold statement, but openly admitting he was selfish is the first step in trying to make things right, to be the family-man that he didn’t previously have time to be. It’s quite heart-warming to see that.

Even Moonwalkers have faults and it’s good that he was able to recognise and admit to his, even if it had cost him a marriage by then.

This is a real human story and that is important. It’s not just about the glitz and the glamour and the almost untouchable superhero status of the Apollo astronauts, it’s real, and that’s what makes this film for me.

Possibly one of the most revealing, and touching, moments for me, was just a small, non-fanfared scene in the film when Gene Cernan is back at Kennedy Space Centre (KSC). His voice catches as he says that it’s all so different now and that he wished had hadn’t come back that day.

Having watched KSC change after the shuttle programme, and having friends who’ve seen their facilities stripped bare and demolished, it really struck a chord with me. That was a very real emotion from him.

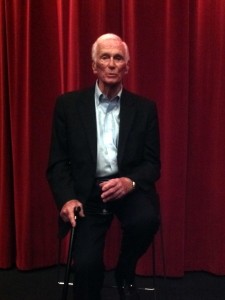

Things were about to get even more “real” – positively incredible – when moments after the credits rolled, the man himself, Gene Cernan entered the theatre to say a few words.

“You created my legacy” he says, thanking the crew for all their hard work and professionalism “I can’t keep going round waving a flag and saying ‘look what I did’”.

Having been initially sceptical of the idea that there could be an entire film about him, director Mark Craig and his team have won him round, showing that it’s his story, not just those final footsteps on the Moon that make this special. “I’ve been extremely lucky” says Cernan, “maybe the luckiest guy in the world”. With a seat directly in front of his stool, I’m feeling pretty lucky myself.

“Final steps of Apollo, not Last Man on the Moon, that’s probably what the title should be” he says. “It’s the path ahead that counts”.

He talks about the archive footage in the film, giving special praise to the person that sourced it – a young chap named Steve (Stephen Slater) stands up and gets a ripple of applause – “it opened up a whole new world to me” says Cernan.

The striking footage of the T-38 that crashed with his friends aboard, Cernan had never seen before the film. “So much that I missed even though I was there” he says. He’d been flying just behind them that day “they wouldn’t tell us [what happened] until after we landed” he said.

Cernan spoke about looking back at the Earth when you’re no longer going round it, but you’re heading out to rendezvous with another body, the Moon. There are two things that you notice, he says, “First, it gets smaller very quickly, second, it’s turning on an axis”. Looking back you see the Earth “surrounded by the blackest black you can conceive in your mind – the endlessness of space and time, the endlessness of time, and the Earth is within this endlessness of time”.

Of the Moon he says that it is “technically, philosophically and spiritually different”.

“You’re trying to understand where you are at that moment in time and space.”

The astronauts didn’t sleep very well on the Moon, even though the flight surgeon told him that the two things they needed to survive were rest and water. “How can you go all the way to the Moon, only be there for three days, and waste time sleeping?” he asks (quite reasonably), “but we had to”.

As if sleeping wasn’t going to be tough enough, they were in daylight all the time. “The only way we could make it dark was with shades, but had to pull the shades up to see where we were – the flag was there” he says, adding he “needed to know that this moment was really happening”.

They slept well on the way home he says, “we only had one thing left to worry about and that’s whether the parachutes are going to open”.

As he talks about having to make sure those moments on the Moon were really happening, I find myself in a similar position. Only twelve people have ever walked on the Moon, only eight of them are still alive, and yet here’s one of them – one of only three people to have been to the Moon twice – sitting in front of me. I realise I’m incredibly lucky, but I also pleased to see that this film has captured his story so well that many more people will get to share it, even if not in person like we did.

As he talks about having to make sure those moments on the Moon were really happening, I find myself in a similar position. Only twelve people have ever walked on the Moon, only eight of them are still alive, and yet here’s one of them – one of only three people to have been to the Moon twice – sitting in front of me. I realise I’m incredibly lucky, but I also pleased to see that this film has captured his story so well that many more people will get to share it, even if not in person like we did.

Before we retire for drinks, Cernan’s step-daughter Danielle is keen to say something. “I’m watching this as a mother and as a daughter – it really is a story that you all have captured so beautifully” she says. “He might not express that, but there are so many moments at home, there have been tears. We are all so grateful, you have done a great job”.

If that’s not praise, I don’t know what is.

There’s probably not much I can say to follow that, other than to add that this is a really intelligently made film, which takes a story that was always going to be of interest to me, and still surprises me with its craftsmanship, tender moments, and attention to detail. If you get the chance, space fan or not, go and see it.

Last Man on the Moon is a documentary film from Mark Stewart Productions. It’s currently doing the rounds of film festivals (do catch it if you can) and it is hoped that a distributor will pick it up for general release. I managed to catch Gene Cernan during the reception and recorded this short interview with him: