Sep

27

Amazing Encounters: Valentina Tereshkova

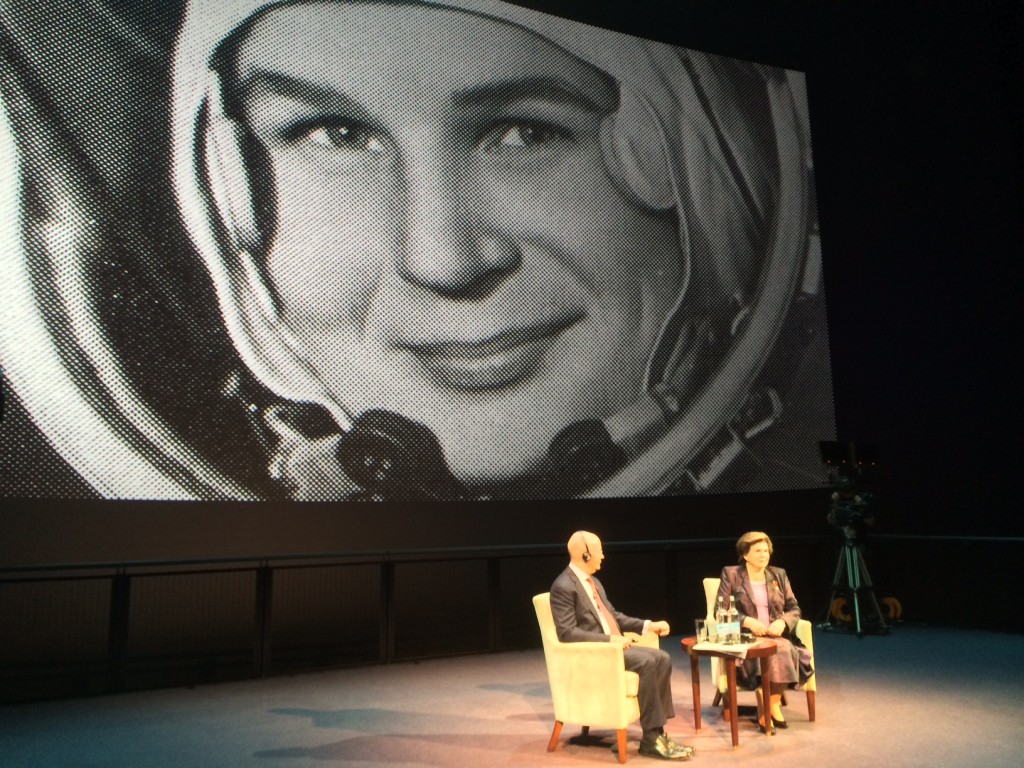

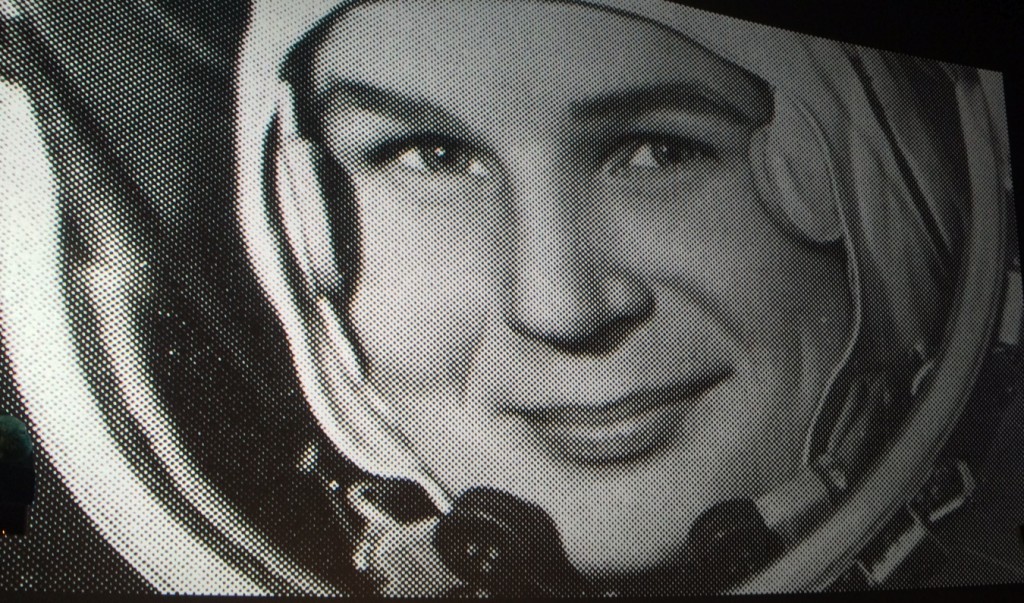

Cosmonaut Valentina Tereshkova – first woman in space, and only female to have done a solo spaceflight – was always going to be on my list of heroes. So as I walk into the large IMAX auditorium at the Science Museum and take a seat for a special Q&A session with her, I can barely sit still. Projected on the screen is a huge black and white photo of her in her space helmet. It’s a wonderful image, and I hear the people in the row behind me echoing that thought.

She enters, with Science Museum Director Ian Blatchford, and I pop on the headphones connected to a small device that will supply a translation of her words. It’s safe to say I’m excited about what I’m about to hear. And I’m not disappointed. In fact, I’m mesmorised. Valentina Tereshkova is cool.

She’s funny, occasionally self-deprecating, and she’s also kinda badass (if that’s not too crude a word to use about a living legend). Here she is sharing her story, right in front of me. I did my best to take notes so that I could share it with you.

“Before life as a cosmonaut, what did you want to be?” asks Blatchford. “Is it true you wanted to be a train driver?”

“Every child thinks about what they would like to be”, she says. “I was from the war generation, we dreamt about peace – we wished for a time we didn’t have to see our parents cry”. Tereshkova explains that when she was young, she lived quite close to a train station, and would watch the trains go by on the way to Moscow and other places. “They must be so lucky” she thought, referring to the fact they got to see so much. Her mother was sceptical about her following this line of career ambition. “Maybe something different?” she suggested.

After Yuri Gagarin flew to space, there was no boy or girl who didn’t want to be a cosmonaut she says. She joined a sky-diving club and all the sky-divers and parachutists thought that they should be the ones to become cosmonauts. On the other hand, all the pilots were convinced that they should be the first cosmonauts.

Tereshkova was invited to Moscow, where she underwent rigorous check-ups and tests, before being recruited as a potential cosmonaut. It was all highly confidential. She said goodbye to her mother, and made up a story about participating in a parachuting tournament.

When the newly selected cosmonaut candidates passed Gagarin in the corridor, “we looked at him as though he was God” she says. “We tried to touch his sleeve” and he asked them “why are you trying to stroke me?!” They explained their story and he showed interest in them.

In the 1960s there had been years of confrontation between the US and the USSR, and there was a lot of competition with regard to space. Tereshkova said that they knew the US was also training women, “but the USSR outdid America again”. On 16th June, 1963, she went up into space.

They had just two years to train – “it was rather difficult, a lot of work” she says, “and we had very limited time”. “We had to say bye to ‘living’ on Earth – we were at Star City, 40Km from Moscow – there were no weekends, and no entertainment” she recalls.

Valentina Tereshkova’s capsule, Vostok-6. Credit: Kate Arkless Gray

Tereshkova was due to fly the week earlier than she did, but there was a lot of solar activity and so the flights were shifted to a later date due to the additional radiation risk. Ahead of her launch, on 14th June, Valery Bykovsky launched on Vostok 5. As with Vostok 3 and 4, the two craft came close to one another and established radio contact in space. Tereshokova’s Vostok 6 launching on 16th June, and when they finally made contact she said “Valery, let’s show that we are okay and we are enjoying the view, let’s sing a song”. “I am not a singing bird” came Bykovsky’s response, “you sing, I will be listening”.

Tereshkova says that she and Bykovsky are still in touch to this day, and when she sees him, she reminds him that he wouldn’t sing with her, “I still don’t want to sing with you!” comes his response, but the ways she tells it, it sounds as though it’s all in good humour.

Tereshkova is asked about the emotional side of spaceflight and there’s an immediate sparkle in her eye. “I love the non-technical speak” she says. “When I was accelerating and the rocket was rising from the Earth I was shouting ‘skies – take off your hat! We’re coming’”. Gagarin asked her “have you forgotten the sailors?” For sailors a woman was a jinx to a ship, and he was saying ‘don’t jinx your flight’, she explains. He laughed a lot about this afterwards –asking “where’s the hat?”

When Tereshkova flew over Yaroslavl Oblast, where she was from, she felt emotional knowing that her mother was there, but quickly realised that she was so busy with the flight that there was “little time for emotion”.

At the time that she flew, her mother, Elena Tereshkova, had no idea that her daughter was a cosmonaut (her father, Vladimir Tereshkov, was killed in Finland while Valentina was just two years old). When one of the neighbours came round shouting “Elena! Your daughter is in space!” her mother calmly replied “you must be dreaming, she is skydiving”.

In fact Tereshkova had written ten letters before her trip, and asked for them to be sent on her behalf. Some sources claim that her mother had been reading one of Tereshkova’s letters about the sky-diving tournament when she received the news from her neighbour. The family didn’t own a television at the time, so it was only when the neighbour brought Elena round to see it for herself on television that she found out.

RIA Novosti archive, image #612748 / Alexander Mokletsov / CC-BY-SA 3.0

All cosmonauts were made to report back after their flight, and when Tereshkova began speaking, in front of Soviet Leader Nikita Khrushchev, she heard her mother’s voice: “Aha! She deceived me”. Krushchev apparently also heard this, going up to her mother to say “please forgive her, it’s her first mistake..”

“..but she was skydiving, she had to parachute” he added.

Vostok craft are different from the current Soyuz capsules – rather than land inside the capsule, you had to eject at around 7Km up and parachute down.

Bykovsky landed in Kazakhstan, but with no aerodynamics, “you could land anywhere” says Tereshkova. She ended up landing in a field in the Altai Region. “I had to be different, as a woman” she says with a smile.

When she landed in the fields, with the aid of her parachute, the women in the field came and said “come on, we will feed you”. She wanted to give them something, and so she handed out some of the space food that she had, which got her in some trouble. “I gave some away – we don’t have to tell everyone” she recalls answering when the agency asked her how many tubes of food she had.

Tereshkova was lucky to have landed at all. A mistake was made with the navigation software on Vostok 6, which, had Tereshkova not spotted it in time, would have seen her launched further and further into space with no way back. Thankfully she did notice, and Sergey Korolev (Head of the Soviet Space Agency) and Yuri Gagarin calculated a new landing algorithm, which she inputted, ensuring she did get back.

Tereshkova says that Korolev was known for “scolding us as much as loving us”. He gathered everyone to find the culprit – the person responsible for the mistake, and found them, but Tereshkova helped save him. On her return, Korolev said “My darling seagull, don’t tell anyone. Everything went well”. (“Seagull” – or “chaika” in Russian – was her call-sign).

“I kept mum” says Tereshkova, on the condition they didn’t punish him, but on the 30th anniversary of her flight Evgeny Vasilievich, the engineer in question, chose to come clean about it saying “people need to know the truth”. Tereshkova says she was “horrified” when he did this, as she had promised Korolev never to say anything.

Someone asks Tereshkova whether her flight was seen as a triumph of engineering and science, as well as a personal and national, triumph? “Naturally” she replies. “Having women in space – showing that a woman’s body would act in the same way as a man’s body”, she talks of her ballistic re-entry “9.5G – it is heavy going” she says. “Each flight was a test – a trial, for the body and science” says Tereshkova” she says. “The first flights allowed us to put in our comments and to perfect the craft.”

Tereshkova explains that the cosmonauts of the time didn’t realise the level of “popular love” that they would receive upon their return. When she had her daughter she got many letters telling her that she should give her daughter a “space name”. Instead she honoured her mother and called her daughter Elena. “She’s a doctor – my happiness, my joy” says Tereshkova. She speaks of the children and grandchildren of other cosmonauts and we learn that Alexei Leonov’s daughter “treats her parents well”, which you can tell is important to Tereshkova. “Our space fraternity tries not to betray each other” she says, “we stay loyal”.

Sergey Korolev had the idea to fly an all female team recalls Tereshkova. She indicates that they had been training and preparing for such a flight around 1965, but in 1966 he died. “It was a huge tragedy to lose such a designer, scientist, visionary” she says. When people looked at his plans “there was pure chauvinism” she says, “we were pushed aside – it was unthinkable to send women”. She tried to let it go – “we were bitter and sad, but still wanted to continue – there was a new craft, Soyuz”.

But with the tragedy of Vladimir Komorov’s flight – Soyuz 1, and then Soyuz 11 ending in disaster, with the capsule depressurising during re-entry preparations, killing all three crew members, the female cosmonauts were told “we won’t be risking your lives”. They were dismissed. “This is our sad story” says Tereshkova.

But with the tragedy of Vladimir Komorov’s flight – Soyuz 1, and then Soyuz 11 ending in disaster, with the capsule depressurising during re-entry preparations, killing all three crew members, the female cosmonauts were told “we won’t be risking your lives”. They were dismissed. “This is our sad story” says Tereshkova.

After Tereshkova’s flight it took 19 years for the Soviets to send another woman into space – Svetlana Savitskaya flew in 1982. (The US put their first female astronaut – Sally Ride – into space a year later – in 1983, 20 years after the Soviets flew Tereshkova.)

During the opening celebrations for the Cosmonauts exhibition, which is currently on at the Science Museum in London, Museum Director Ian Blatchford and Tereshkova made a deal to go in to space together. “Ian will sing Russian folk songs in space” she says, “and she will sing English ones” says Blatchford.

“Shall we start now?” Tereshkova asks enthusiastically. “Nyet!” replies Blatchford, firmly. “So, you can’t trust a man really, can you?” says Tereshkova, raising a laugh from (at least) the female members of the audience.

What of the future? “We desperately need new engines and spacecraft” says Tereshkova. Getting to Mars “could become a reality sooner if scientists from other countries all work together – only then could we do it sooner” she says.

“It was my dream to go to Mars” says Tereshkova “I’m quite happy to go there one way, to stay there”.

“It is such a shame that time flies.”