Mar

2

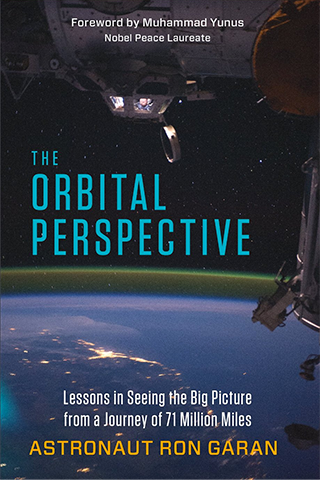

Astronaut Ron Garan. Image Courtesy of NASA

Genial astronaut Ron Garan reminds us to put away our cynicism and rekindle the “anything is possible” attitude we had as bright young dreamers before the realities of everyday adult life came to bear…

In his new book, The Orbital Perspective: Lessons in Seeing the Big Picture from a Journey of 71 Million Miles, Ron Garan draws not only on his time in space – from which the book, and the central premise take their name – but on all the partnerships, and international collaborations that were needed to get him there. He uses the International Space Station (ISS), an enormous feat of engineering and international bridge building, as an example of what can be achieved if we all pull together in the same direction – and wonders what could be achieved to alleviate the imbalances and suffering at ground level if we could capture the same spirit of collaboration and focus it on these issues.

As a huge fan of human spaceflight, I couldn’t help but get goosebumps reading the sections about his mission to the ISS, especially as he describes his first launch on space shuttle Discovery. Having seen (and felt) shuttle launches in person, I am always gripped by these personal accounts of launching into space, so I enjoyed living vicariously through his words as I myself was jostled about on the tube to work.

As a huge fan of human spaceflight, I couldn’t help but get goosebumps reading the sections about his mission to the ISS, especially as he describes his first launch on space shuttle Discovery. Having seen (and felt) shuttle launches in person, I am always gripped by these personal accounts of launching into space, so I enjoyed living vicariously through his words as I myself was jostled about on the tube to work.

These accounts of his time in space are not the main focus of the book, but rather they help in bringing you along on his journey of discovery that has led to this current goal of connecting people, organisations, nations, and businesses to share experiences and knowledge and ultimately, to help change the world for the better.

While numerous astronauts have spoken of the wonder of seeing the Earth from above, with some speaking about the way this has profoundly changed their outlook (the ‘overview effect’), Garan is keen to point out that the orbital perspective is about more than just seeing the Earth from above and contemplating it differently – it requires action. He’s also quick to reassure you that you don’t have to have experienced being in orbit to understand – or to take – an orbital perspective (though I’d be up there in a shot anyway, given half the chance).

Garan’s orbital perspective is all about realising that we are all interconnected and sharing a ride through the universe together on spaceship Earth – our Fragile Oasis. Realising that (and I quote The Hitchhiker’s Guide To The Galaxy here) “you might think it’s a long way down the road to the chemist, but that’s peanuts to space”.

We’re all in this together – if you can step back far enough to see the picture in global, planetary terms, rather than getting lost in teams, groups, cliques, nationalities and the like. It makes perfect sense when you look at it that way (though in the midst of an election campaign things never seem quite so clear!).

I’ve certainly heard astronauts say “you can’t see any borders when you’re in space”, which has always been quite a wonderful, comforting thought. I was quite shocked then, to read that while taking some photographs, Garan had actually been able to pick out the marking of the border between India and Pakistan.

Illuminated human made border between India and Pakistan – Ron Garan/NASA

“Seeing that border from space, a true barrier to collaboration, had a huge effect on me” he writes, then describing the “sobering contradiction between the staggering beauty of our planet and the unfortunate realities of life on our planet for many of its inhabitants”. It was this moment that led him to the idea of the orbital perspective.

Garan describes the orbital perspective as the call to action that comes from the overview effect – that change in perception that astronauts described after having looked back at the world from the unique viewpoint of space.

“The key”, he says, “is ‘we’”. Nothing is impossible if we can connect the right people, use the bigger picture to help us overcome our cultural and political differences, and work together to solve the world’s greatest problems.

As a born dreamer, a person that challenges the notion of “impossible” (until it comes to the laws of physics), and someone who takes pride in making things happen, I find myself quite intoxicated by this idea. It’s exciting, it’s positive, it’s people working together to make things better. I love it.

Before we get too carried away, Garan reminds us that while the big picture is all very well, you have also got to consider the “worms-eye view”. In standing back to ensure that you see the whole picture, you are undoubtedly missing the intricate details that create it. Without an understanding of the realities of life on the ground, no matter how perfect your solutions might seem from afar, they could fail at the first hurdle. You need to ensure that you explore both extremes of perspective in order to identify schemes that can work in the long term, and also improve the everyday lives of people.

It’s not a simple task, but Garan returns to the way that the ISS project was realised and created, using the essential skills and contributions (both physical and intellectual) from two previously warring nations.

It’s not a simple task, but Garan returns to the way that the ISS project was realised and created, using the essential skills and contributions (both physical and intellectual) from two previously warring nations.

He pays tribute to all those who went the extra mile, working to build up the strong –at times vital – personal relationships that allowed Russia and the United States to come together and work as indispensable partners in space. The message is clear – if humanity can put aside its differences and create an orbital space station – continuously inhabited by multinational crews for over a decade – why can’t we achieve other great things?

Garan also turns to the example of nations, companies and intellectuals coming together to help free the Chilean miners in 2010. It was a do or die situation and those in charge were smart (and humble) enough to know that this wasn’t something that they could do alone. With contributions and coordination, including utilising NASA’s experience and knowledge of living in confined spaces, what could have been a deadly national disaster became an incredible international rescue story, touching people around the globe.

There’s no doubting that great things can be achieved, and that we could all benefit from a more global way of thinking, but how do we make that happen?

Garan talks about schemes that are already bringing people together, hackdays like NASA’s International Space Apps Challenge and organisations like Engineers Without Borders, his enthusiasm is infectious. He also talks about the need to ensure that we don’t just double up our efforts, but rather coordinate and work together to build even more impactful solutions.

Garan talks about schemes that are already bringing people together, hackdays like NASA’s International Space Apps Challenge and organisations like Engineers Without Borders, his enthusiasm is infectious. He also talks about the need to ensure that we don’t just double up our efforts, but rather coordinate and work together to build even more impactful solutions.

This is an inspiring book that I would encourage everyone to read – I’ve already passed it on to the director of the charitable foundation that I work for – and there are definite lessons to be taken from it. Not only in the big picture sense of making the world a better place, but there are many everyday lessons that could make the average workplace better. Issues that he identifies that particularly affect non-profits – quick turnover of younger staff members who come to do something good and experience new places for a while, before being enticed away with higher paying careers – can have an effect in many places.

The communication channels between vibrant directors and leaders with a strong vision and those on the bottom rungs of organisation, who may be full of new ideas and perspectives, need to flow. All too often there can be a sticking point in the hierarchy and bureaucracy of managers in-between.

Garan also opens our eyes to headline-grabbing charitable projects that may not have the required infrastructure behind them to ensure that the initial benefit lasts. A striking example Garan explores is why charities may prefer to install new water-pumps, rather than spend money ensuring that existing ones can be restored and maintained for many years. It’s all about how we measure success, and a system of funding that may be hostage to the need for headlines in order to raise new funds.

With the ever-increasing disparities in wealth around the globe it is obvious that the system is broken. Garan’s book reminds me of the optimism and hope that I had as a child, and that I still have, despite various battle scars from life.

Garan makes us believe in the potential to make a difference, together, but I guess my biggest question, having read the book, is “what can I do?” – I’m not an engineer, or a coder, but I do have enthusiasm and ideas. I’m still working on how I can be useful, so if you have the answer, let me know!

The book is (not wanting to sound dismissive) idealistic, but importantly he ensures there is substance behind the idealism. Whether Garan’s orbital perspective has the strength to help fix our global problems remains to be seen, but it’s certainly a step in the right direction and I’ve got every confidence in him to inspire people to help make a difference - I can vouch for his personal charisma and charm.

Viewers of the X-Files may recall a poster in Fox Mulder’s office, which sums up my feelings about the orbital perspective and it’s energetic optimism about our ability to work together and change the world: “I want to believe”