Nov

29

Is Curiosity the key to life on Mars?

It’s the ultimate detective story: The case of the missing molecules on Mars. But in this mystery it’s not Sherlock Holmes playing the master detective, but a team of scientists studying the origins of life.

“Our story really begins more than thirty years ago when Viking lands on Mars and tries to detect organics” says NASA’s Dr Chris McKay, the renowned astrobiologist, actively involved in the search for Martian life.

Organics are the building blocks of all life on Earth, and their presence on Mars may provide evidence that the planet could have supported life. Viking carried a very sophisticated instrument able to detect and characterise organic compounds in the soil.

“Much to our surprise what Viking told us was that there are no organics there at all” says Dr McKay.

Even in the absence of complex biological organics, Viking had been expected to detect traces of organic compounds due to meteorite impacts: “It was a real mystery” says Dr McKay, “why weren’t there organics in the soil of Mars?”.

For thirty years the puzzle remained, but much like a criminal cold-case, solved thanks to new forensic techniques, the results from NASA’s Phoenix mission in 2008 shed new light on the case.

Phoenix discovered that on Mars, the element chlorine was not in the form of harmless table salt, but instead in a very unusual type of molecule called ‘perchlorate’. In this form each chlorine molecule is attached to four oxygen atoms making it very stable on the freezing plains of Mars.

With this new finding in mind, scientists re-examined the original results from Viking.

In fact Viking did detect small amounts of an organic compound called methylchloride, but researchers struggling to explain its presence put this down to contamination from cleaning fluids.

To detect the presence of organic molecules, Viking heated-up the Martian soil samples, “like cooking something until it burns and you smell what’s coming off” explains Dr McKay. An unfortunate consequence of technique was that by heating the samples, the perchlorate split into its reactive form and destroyed the organic compounds that scientists were searching for.

Although initially dismissed as contamination, the detection of methylchloride proved to be vital to solving the mystery. When scientists conducted similar tests on Earth, heating the samples as Viking had done, they produced similar results. Adding perchlorate to soil from the Atacama desert in Chile (a Mars analogue site) resulted in most of the organics being destroyed, leaving only the small fraction of methylchloride.

Dr McKay sums up the case in simple terms: “the very thing we’re looking for was burned up by a molecule we didn’t realise was there”.

With this scientific cold-case cracked: how will this knowledge affect future Mars missions? The problem remains that heating samples of Martian soil may have unintended consequences, so a new analysis method is required.

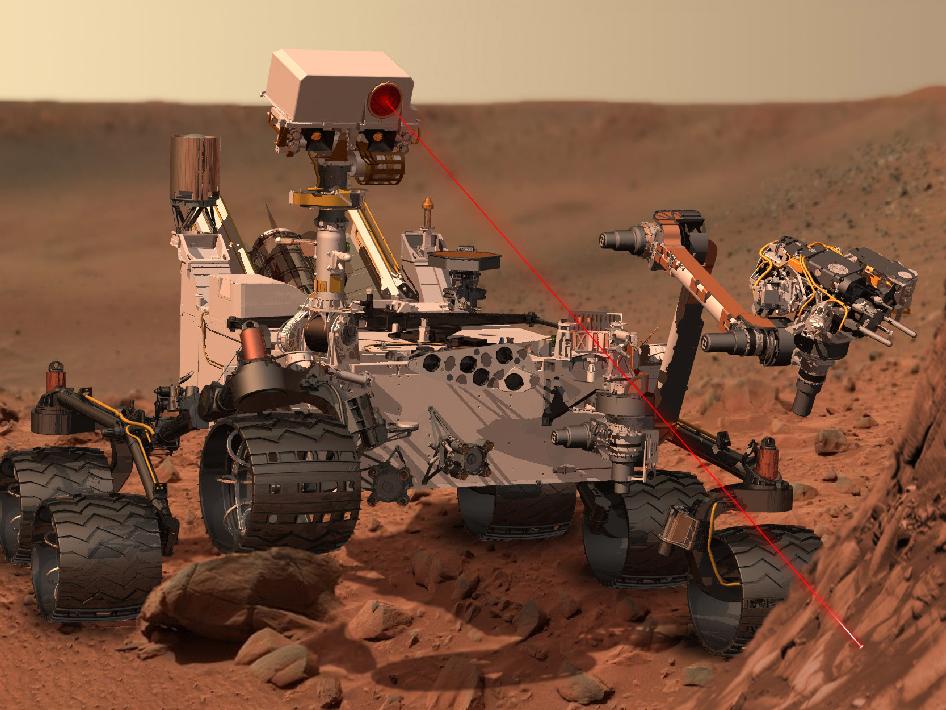

The Mars Science Laboratory, nicknamed ‘Curiosity’, is carrying an instrument that is capable of soil analysis using a liquid extraction system, which means samples don’t need to be heated.

“You might think that we were very clever in deducing that, but no, we were just lucky” Dr McKay says candidly. “We’d planned that liquid extraction for reasons that had nothing to do with perchlorates, and now we’re in a lucky position that we’re going to fly exactly what we should be flying to see the organics”.

Since Curiosity successfully landed in August 2012, there has been much excitement in the astrobiology community about what may be revealed. “Finding organics at all would be ground-breaking” says Dr Lewis Dartnell, an astrobiology research fellow at UCL. “We expect them to be there, but haven’t been able to sniff them out yet. Once simple organics have been detected, follow-on missions will focus on finding firm evidence for life”.

“No one test or experiment will prove Martian life conclusively” advises Dr Dartnell, raising concerns about media sensationalism. Curiosity is not actually designed to find life, only to test whether the red planet could have supported it. So people following current internet rumours of an “earthshattering” announcement from NASA will likely be disappointed.

Despite this, the idea of life elsewhere in the solar system is a tantalising possibility: “I think that the detection of life on another world beyond the Earth would be of profound significance, alongside realising that the Earth isn’t flat and that our planet orbits the sun” says Dartnell.

After all these years of searching, what does Dr McKay think we’ll find? “If I was guessing I would say that the chances of finding anything alive on Mars today, is very small, but the chances that we’ll find evidence that there was life in the past is very high”.

“That’s what I have my sights set on; not finding something alive and squirming in the soil now, but evidence of something that was alive once.”

For now, the jury’s still out on the question of life on Mars, but with new instruments aboard Curiosity, could the wait for evidence it could have been habitable almost over?