Oct

16

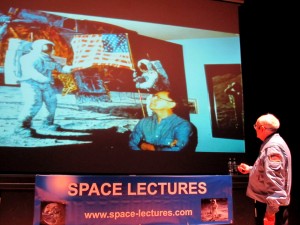

Captain Alan Bean was the fourth of only 12 men ever to walk on the Moon. I was lucky enough to hear him share some of his stories, and speak about the way he is trying to capture his experience through the medium of painting. Here are some of the highlights of the talk he gave in Pontefract on 12th October 2013.

Alan Bean the Artist

Alan Bean went to night school to study art. He was training to be a space shuttle commander at the time, but he decided to give that up, saying that he’d had his chance. He’d gone to the Moon and, in his words, “there were others that could command the shuttle just as well as I could”. Some people thought he was having a mid-life crisis at that point, others thought that art was not a worthy subject, but he continued. “We’re all different, we should preserve that” he says. He speaks passionately about his work, of capturing memories of the Moon in a way no-one else can. I think the stories about his art deserve a post of their own.

Alan Bean the Apollo Astronaut

Getting to the Moon was a job done by 400,000 people, but they were not 400,000 geniuses he says, just 400,000 people that worked together to make it happen. “Every flight to the Moon had to start somewhere; every impossible dream has to start somewhere”.

Test pilots were the ones that had flown things that were as close to being a spaceship as possible. Alan Shepard, John Glenn, Deke Slayton, they all came from that test pilot background before they were astronauts. “I had never done anything impossible before” says Bean, “I had never even tried to do anything impossible before”. When he started, he was worried that everyone was going to be a genius and he’d have a lot to learn from them all. After meeting someone and realising that they were no smarter than he was, he got more worried. If they were like him, and he knew he couldn’t do it, how could going to the Moon be possible?

“I never heard anyone saying we couldn’t do it” says Bean, there was more “wow, that was a mistake we made, we shouldn’t do that again”.

All humans make mistakes he says, “we’re trapped by who we are”, they just had to be willing to pay the price.

Bean said that he knew from calculus at school that he wouldn’t know how to point a rocket at the Moon. Others could, but they can’t fly a spaceship. They all had to work together to make this happen.

Things didn’t always go smoothly. Bean tells us the story of his suit-testing. In order to check various things they hoisted him up in the air whilst wearing it to see how he could move in it. It was padded, but not enough, and while the suit was held in the air, Bean himself inside it was not. “Owch.” They realised their mistake and tried putting more padding in “it wasn’t enough”. Then they tried filling the suit with water so that he could float inside but “you can’t float standing up”. After various attempts they tried training in water (much like the astronauts do now to train for spacewalks) so that when he got to the Moon, he knew what to do.

Things didn’t always go smoothly. Bean tells us the story of his suit-testing. In order to check various things they hoisted him up in the air whilst wearing it to see how he could move in it. It was padded, but not enough, and while the suit was held in the air, Bean himself inside it was not. “Owch.” They realised their mistake and tried putting more padding in “it wasn’t enough”. Then they tried filling the suit with water so that he could float inside but “you can’t float standing up”. After various attempts they tried training in water (much like the astronauts do now to train for spacewalks) so that when he got to the Moon, he knew what to do.

Alan Bean on the Moon

Bean was asked by his superiors what he thought he was going to do on the Moon. “Put the flag in, collect some rocks, talk to the President, put the TV camera on and see how high we can jump” replied Bean. “That’s what we thought you thought” they said before reminding him that they had to be explorers when they were up there.

The astronauts had to learn about different rocks so that they knew what to look for on the Moon.

“But that’s geology” he grumbled, “maybe you shoulda got geologists and taught them to fly!” After a few days complaining they settled into it. “I’ve probably got a doctorate in geology” says Bean, “I didn’t even want it, but I quite like it now.” They trained in places like Hawaii, where if you covered the ground with two feet of graphite like you get as pencil sharpener dust, it would have been like the Moon.

They thought that they would find craters two billion years old, but they didn’t find that. Instead they found everything was around 3.5 billion years old – as though nothing had really happened to the Moon since then.

“We’d love to find a great big relic, a whole stack of diamonds – something – not just rocks” says Bean. He admits that they considered taking an arrow head up with them as a practical joke, placing it on the Moon in such a way that mission control would see it. He’s glad they didn’t do it though, there are enough people with conspiracy theories and as he says “I love scientists, but they wouldn’t have been amused”. “They probably wouldn’t have let us back in!”

Getting to the Moon

We thought we would lose more crews trying to get to the Moon than we did, says Bean. We have three spare command modules and rockets. “We knew this impossible dream wouldn’t be easy.” Neil Armstrong thought his crew had a 90% chance of getting to the Moon and back, but only a 50% chance of actually landing on it, recalls Bean. Armstrong and Bean shared a secretary at work, and Bean remembers how strange it was that they’d been in the office together “then all of a sudden he turns up on the Moon”.

Neil Armstrong confided to Bean that putting the American flag up was one of the scariest moments of the mission. “Why?” asked Bean, apparently Armstrong couldn’t get it deep enough into the Moon and was really worried it might fall over into the dust. He found the centre of gravity for it and carefully balanced it, reportedly saying “as soon as we got it balanced we got away as soon as possible, and we didn’t go near it again”.

Neil Armstrong confided to Bean that putting the American flag up was one of the scariest moments of the mission. “Why?” asked Bean, apparently Armstrong couldn’t get it deep enough into the Moon and was really worried it might fall over into the dust. He found the centre of gravity for it and carefully balanced it, reportedly saying “as soon as we got it balanced we got away as soon as possible, and we didn’t go near it again”.

Originally Bean thought that they would be going to the Sea of Tranquillity like Apollo 11 before them, but they were told that they were going to the Ocean of Storms instead. NASA wanted to prove that they could land near something – Surveyor – but as Bean pointed out with reference to Apollo 11 “we just proved we can’t!”.

They were given an extra two months to find a way to land with pin-point accuracy. The crew and mission control worked on the problem, but the ideas that were first suggested just weren’t working in the simulations. Then someone at the back of a meeting had an idea. They had to find a way to take data from two tracking stations so that they could work out exactly where they were and how fast they were going. That way they could re-programme the computers for landing.

This gave them two problems he says: firstly, there was no way to take information from two places, and secondly “you don’t want to go into the computer when the engine’s burning”. There were no better ideas so as the mission data crept up they were told “you figure out a way to get your data into the computer without screwing up so you hit the Moon”. “That’s the NASA way” quips Bean.

Launching from Earth

“Our rocket” says Bean, referring to the enormous Saturn V that transported him to the Moon, “it was so beautiful”. He speaks of the cryogenic fuel causing ice to build up on the rocket, making it shine. He remembers looking down with pieces of ice falling off “it looked like a breathing animal of some sort – it wasn’t inanimate”. When they launched and it was shaking he wondered if they could keep the rocket together.

“It didn’t look like we were leaving” he says, explaining that it felt like the Earth was leaving them. “It’s leaving us” he thought, and in 10 days time “that thing (Earth) was going to be who knows where”. It was mission control that would have to make the calculations to get them back safely.

He tells us what was going through his head as they were nearing the Moon, “I’m feeling frightened, I can’t do my job when I’m feeling frightened”. He looked back into the module and at the control panels, it looked just like the sim, he felt better. Then he looked back out of the window and back in again, he had to adapt to it.

Just as I’m thinking that this admission of fear is unusual from an astronaut, he comments “I’ve never heard any other astronaut say that”.

Alan Bean on Flying Round the Moon

Bean speaks warmly of his commander saying “Pete Conrad is the best astronaut I ever met”.

Whilst they were up and orbiting the Moon it was Conrad’s job to run the primary computer and Bean was looking after the back-up systems in case they should lose contact with Earth. Here’s the story as Bean tells it (perhaps worth checking out the Apollo 12 transcripts for exact details on the conversation):

Conrad: “It looks like you’re working hard back there”

Bean: “Yes”

Conrad: “But don’t miss the flight. Why don’t you put it down and look out?

As Bean explains to us “He’s my commander, so I did. I looked out of the window”, then came the ultimate question from Conrad. “Al, would you like to fly this thing?”. Conrad explained they could call up a delta V programme and zero things out again to be back on course. Bean knew that mission control was not going to like this, but Conrad had it covered. “Don’t worry, we’re on the dark side of the Moon, they’ll never know”.

You can’t fault the logic and it’s evident Bean still holds this moment dear, “Wow – for someone to think of that – for me…” he says with admiration and humility.

No other commander let their lunar module pilot do that, even when Conrad had told them about the idea.

Any regrets?

When Apollo 14’s Alan Shepard became the first person to hit a golf ball on the Moon Bean asked Conrad “Why didn’t we think of that?”. The answer that came back was simple “we don’t play golf”. Bean thought that they should have done something though, play football perhaps. He can’t go back to correct that in person, but artistic licence has allowed him to imagine the scene in one of his paintings.

“Apollo didn’t do enough things that were fun for humans” says Bean. If we went back, in addition to the science, we should spent 5% of the time doing things that are fun for humans he says. He seems pleased that astronauts on the ISS are finding time to do things like this. He recently met Japanese astronaut Koichi Wakata (who is launching to the station later this year) so let’s hope he passed this message on to him.

Alan Bean on Earth

“When I think of the Earth I think we’re in the garden of Eden” says Bean – joking that it’s even easier to believe that in Pontefract than in Houston!

When the Apollo 12 crew splashed down he thought “Wow – look at that water – so deep and so blue”. They had only been gone 10 days but “we never saw anything going on out there, nothing moved but us three and the spacecraft” he says.

Travelling to the Moon affected him in other ways too: “since I’ve been home I’ve not once complained about the weather – at least we’ve got it” says Bean.

Closing Thoughts

A packed room sat captivated by Bean’s stories, his willingness to share, his art, and his advice (to be covered in a separate post). Going to the Moon is a huge privilege and the great thing is, he knows that. “I feel thankful every day” he says, before leaving us with three wishes:

Light to thy path,

Wind to your sails,

Dreams to thy heart.

We pause for a moment, then applause sweeps across the hall, accompanied by a standing ovation. This man walked on the Moon and there was something very special about hearing all about it first-hand.