Apr

21

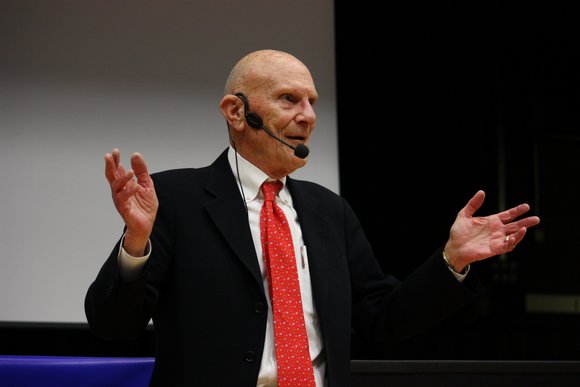

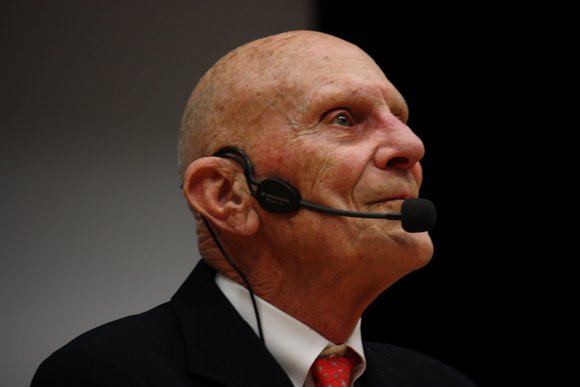

Ken Mattingly – Apollo’s humble hero

“I would encourage you to understand that the people that made Apollo happen, are not here” says Ken Mattingly, self-effacingly. “There wasn’t an airplane big enough” he adds with a wry smile.

Mattingly, command module pilot of Apollo 16 and two-time shuttle astronaut, has come to Pontefract to talk to us thanks to the hard work and efforts of the Space Lectures team led by Ken Willoughby.

He’s softly spoken, keen that that we should understand that whilst the astronauts got the fame, the huge team of scientists and engineers who came together to create the Apollo programme are the ones who deserve our reverence. “Normal people became special” he says, and that’s the power of the Apollo programme, that working together they were able to achieve the extraordinary.

In a few short words at dinner he shows that despite his age, the sparkle is still there. “If anyone wants to talk about space, I’ll keep you awake all night!” he exclaims. I bite my tongue so as not to embarrass myself by leaping up and shouting “me! me! I want to talk about space all night!”

I catch him briefly in the bar afterwards and remind him of what he said. He grins before showing off a surprising level of flexibility by moving his foot towards his mouth. We both laugh and I sense that any concerns he had about coming to the event are melting away. He’s among friends, people who really care about space, rather than celebrity.

Not wanting to waste my brief moment with him I ask him about his wedding ring, apparently lost, then found floating out into space before bouncing off Mattingly’s helmet and pinging back into Charlie Duke’s hand before he left the capsule. He seems a little surprised before saying “that’s Charlie’s story” as though he doesn’t want to take any of the credit for it. I ask him what eventually happened to it, and he rather bashfully admits “I lost it” he says, “on Earth”. He thinks it slipped off while he removed some flying gloves. It seems a rather understated end to such an incredible story, but Mattingly himself is rather understated for a man of such achievement. I could have talked to him all night, but so could everyone else, so I give up my prime position for someone else to enjoy his company. As he headed off to bed he apologises that our conversation was cut short before commenting “what a neat bunch of people”.

The following day we’re gathered in the school hall awaiting his talk and I find myself wondering what he’ll say. I can’t imagine him focusing on his personal achievements or acting the star despite the fact that it’s his presence that’s brought people from far and wide – not just across the UK but from Europe and even the US.

He starts simple, with three questions for us:

- “Who here is interested in space?” – a room full of hands shoot up

- “Who is interested in human spaceflight?” – the same hands fly up once more

- “Who would like to go to space?” – I’m not sure about anyone else, but I raise both hands at this point.

I assume others followed the pattern for the final question because he congratulates us on our “graduation”. We’re ready for his talk.

The Apollo programme is almost as old as I am he says, “ancient history”. We laugh at this joke, but there is a slight sadness in the air as many of us realise that whilst “ancient” is a bit of an exaggeration, “history” is indeed what it is.

Mattingly talks us through some of the history that led to the Apollo programme – “one day we woke up to the sound of beeping from Sputnik” – the country was terrified he says. What do you do to recover from that? You put a man in space, and that’s what the Mercury programme was set to do, but then Russia put a man in space. “The panic was palpable” he recalls.

When Kennedy said that they would send people to the Moon and bring them safely back again by the end of the decade, that only gave them nine years. “The next nine years were total chaos” says Mattingly. They had to recruit a lot of new staff, but people wanted to work on the programme because they thought it was cool.

Mattingly, known as “TK”, uses the large model of a Saturn V that’s on the stage to describe the different stages of the rocket launch.

Finally pointing up at the command module perched at the top he says that when you see the real thing in a museum “it doesn’t look that small, ‘cos it’s empty.”

“Let me tell you, you really get to know people spending two weeks in that little bath tub”. This rare insight into his own experience is coupled with a sparkle in his eye as he remembers his flight.

Back to the rocket – “really a spectacular sight” he says of launch – “that sucker goes up!”

“Frank Borman thought he was commander when he got onboard, but realised within one second he couldn’t command anything – you can’t command that thrust”

Talking about his own flight on Apollo 16 he remembers thinking “we’re still goin’ up, that’s a good sign”.

He had heard about people getting sick in space and started to worry that the first thing he did in space might be to throw-up. As it happened as he got up out of his couch and the first thing he thought was “I’ve been here forever – it’s perfect!” There’s something so genuine about the way he says it – it’s not just a line he reels out at talks because it is what people want to hear – but full of emotion, wonder, and relief.

“You can entertain yourself for a day just throwing stuff” he says, but then adds that “the novelty of floating really wears off after two-and-a-half days with someone in your face all the time”.

Looking out of the window, he thought “this going to the Moon is really neat!” (I’ll say! just a bit!), “but I want to come back and see the Earth – it’s beautiful”.

We get a little more of Ken Mattingly at this point. He shares how as aviators, when you see a thunderstorm, you fly the other way, but when you’re flying over them in space you think “that’s really cute – little sparkling lights”.

“You never tire of looking at the Earth” he says before adding that “the Moon is not beautiful, but seeing Earth-rise over the Moon is beautiful”.

He moves on to talk about Apollo 13, the fateful mission that he was due to be part of, but due to a worry that he had been infected with German measles, was removed from at the last minute (well, 72 hours before it flew, to be exact).

“Apollo 13 was not a failure” he says confidently, “it was the only example of why we succeeded, that you could see”.

“There are moments that catch your attention and they don’t last long, but they are indelible” says Mattingly.

He explains how a couple of weeks before launch they had one last weekend when they could go home. When he got back to the Cape he found that one of the children at the picnic he’d been at had come down with German measles. If you’ve been exposed to measles before, then you’re okay, he says, “and what adult hasn’t been exposed?”

“Well, they found me.”

They took blood samples from him twice a day for testing. He says they took so much blood “I was afraid if they launched me I would be anaemic”.

Eventually they decided that they couldn’t take the risk with him. He couldn’t believe it. He references the film version of Apollo 13 “let me tell you – his portrayal of feeling sorry for self was terrible!” – implying that he felt much worse than even the film suggested.

He recalls sitting on the floor in Mission Control between the CapCom and the Flight Director because there was no space for him there.

He recalls sitting on the floor in Mission Control between the CapCom and the Flight Director because there was no space for him there.

During the flight the Apollo 13 crew were sending down pictures from the LEM. He was watching in the VIP area, and no one else was really around. Just him and one other guy – it wasn’t like the previous launches when those spaces had been bustling with people. The crew said goodnight and the other guy said to Mattingly “you look like you need a beer” before going off to get his briefcase. Then Mattingly heard a voice over the air to ground comms system and, in his words, “the whole world changed”.

The team were together in minutes and within two hours the parking lot was crowded. It was the middle of the night but there were heads in every office he said. There was no drill to practice this but people heard the news on the radio and came straight in to help – some of them didn’t go home for 4-5 days.

When an accident occurs they are trained not to get fooled by bad instrumentation; “it can lead you to do bad things”. When the Apollo 13 incident began their first thought was to check the instruments and they thought it was that, but then they heard a voice asking “when was the last time instrument failure made of cloud of stuff out the sides?”.

This was right about the time they were due to do a shift change from Glynn Lunney to Gene Krantz. They decided to split into teams – one to get them safe and one to get them home.

“Talk about confusion and pandemonium” says Mattingly, “everyone had an idea for someone else, but not for themselves”. According to him, Glynn Lunney found specific tasks for specific people and that was when the “machine starts to run”.

Having earlier admitted that he had done his best to “cheat Swigert out of SIM time”, Mattingly says that the future relies on simulations of unrealistic problems. They were criticised for doing them, but he remembered doing a Sim where they had used the LEM as a lifeboat. When they called up to the crew they were already doing the “LEM lifeboat” procedure. The command and service module was going to die in less than an hour.

The crew moved into the lunar module hotel – three in the space of two – but without electricity, it was good to have an extra body for heat.

There was frost inside. All the electronics were behind panels that were below freezing. They had not been qualified for those conditions.

They worked through options for getting the crew home. A direct return would use all the propellant that they could get their hands on and there was no room for error. Where would they land? They didn’t know.

If they went around the Moon with life support only, saving energy by shutting all computers down, would they be able to align? They decided to leave the relevant equipment off until the last minute, when they had some information to put into it to help them align.

If they did this, they would have an Atlantic landing, but all the recovery crews were in the Pacific. They found one more manoeuvre that would allow them to get to the Pacific – then it was lights out, and miserable cold.

All the contractors were ready to take calls about any of their equipment – not just the staff, but the head’s of the companies were answering the phone and ensuring NASA has all the information they needed about their equipment.

Mattingly recounts an incredible story about a vital piece of equipment – the inertial measurement unit (IMU) which measures the spacecraft’s velocity and orientation – that had never been tested outside of temperature limits. Would it work when they switched it back on? They had no test data because they never imagined it would have to work in such cold conditions.

A NASA contractor heard the news about the drop in temperature and the concern that equipment might not work. He called his boss to admit something he’d done wrong, and had previously covered up. When a snow storm hit and their factory had been closed due to the cold, the last thing he was meant to do before leaving was to take this piece of equipment from one building to another. He put it in his truck, but then forgot about it, leaving it out in the cold. Embarrassed by this mistake, he decided rather than owning up, he’d sneak it back in to the factory and leave it on the table it was meant to be on.

Knowing it was an important piece of equipment; he did go back and check with the testers that they hadn’t found anything unusual on their next text. They said “no”, so he could sleep at night.

When the Apollo 13 crisis was unfolding, he realised that his boo-boo might actually give them a useful data point, so he came forward and admitted to his boss what had happened – not only owning up to having done something wrong, but to covering it up as well.

That one data point said that it might work, and there was a great sense of relief says Mattingly.

“That kind of free communication brought them home” he says.

You have to remember that mid-20s was the average age of people in the Mission Control Centre. “Sometimes the social interactions were not always smooth – but everyone wanted success.”

And with that, Mattingly opens the floor to questions, but not before we gave him a standing ovation. I watched him as we did, at first relieved and smiling, and then again, that sign of the humble man he is, slightly uncomfortable with the level adoration focused on him.

Ken Mattingly seemed delighted to take questions – again, it was something that helped take the entire spotlight off him, and made him feel that the words he was sharing were genuinely those we wanted to hear. First up, given that he’d said floating round in space was boring with people in his face all the time – how did it feel when he was on his own?

“Wonderful!” he exclaims, without hesitation.

He then shares the story of how the original Apollo 13 crew had made a special tape with the three of them talking, and that they were going to play out in the LEM to make it sound like they were all in there. While the tape was playing he was going to refuse to answer any calls from mission control as they did so – to make it seem like all three of them were headed to the Moon! Obviously they never got to do that, which is a shame, but again makes me smile that these heroes all have a sense of humour.

“What was it like to ride two launch systems?” someone asks, “what’s the difference between Saturn V and Shuttle?

“Stark terror, and isn’t this cool” he says. “Really really different!”

A younger member of the audience asks what his favourite space food was… “I don’t think we’ve created that yet” he says “it’s not like eating at home”.

Finally he is asked how he feels about the “Spam in a can” accusation that test pilots levelled at the astronaut corps. “Test pilots made fun of the space programme” he says, adding that “pulling Gs is fun, but flying is zero G is more fun” in a characteristically diplomatic way.

It’s been a delight listening to Ken Mattingly, I only wish I’d had more one-on-one time with him – not only because he’s an Apollo astronaut (and why wouldn’t you want one-on-one time with any of them?) but because I feel that he (and I) would be more comfortable in that setting.

Ken Mattingly is a humble, wonderful, astronaut, who was lucky enough to look out of the window, and smart enough to realise that it was the work of thousands of others that enabled him to do so. What a gent.