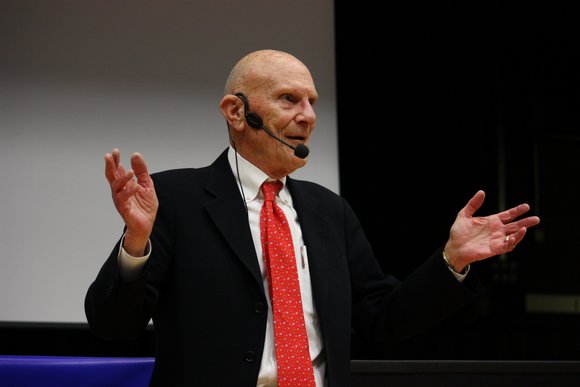

“I would encourage you to understand that the people that made Apollo happen, are not here” says Ken Mattingly, self-effacingly. “There wasn’t an airplane big enough” he adds with a wry smile.

Mattingly, command module pilot of Apollo 16 and two-time shuttle astronaut, has come to Pontefract to talk to us thanks to the hard work and efforts of the Space Lectures team led by Ken Willoughby.

He’s softly spoken, keen that that we should understand that whilst the astronauts got the fame, the huge team of scientists and engineers who came together to create the Apollo programme are the ones who deserve our reverence. “Normal people became special” he says, and that’s the power of the Apollo programme, that working together they were able to achieve the extraordinary.

In a few short words at dinner he shows that despite his age, the sparkle is still there. “If anyone wants to talk about space, I’ll keep you awake all night!” he exclaims. I bite my tongue so as not to embarrass myself by leaping up and shouting “me! me! I want to talk about space all night!”

I catch him briefly in the bar afterwards and remind him of what he said. He grins before showing off a surprising level of flexibility by moving his foot towards his mouth. We both laugh and I sense that any concerns he had about coming to the event are melting away. He’s among friends, people who really care about space, rather than celebrity.

Not wanting to waste my brief moment with him I ask him about his wedding ring, apparently lost, then found floating out into space before bouncing off Mattingly’s helmet and pinging back into Charlie Duke’s hand before he left the capsule. He seems a little surprised before saying “that’s Charlie’s story” as though he doesn’t want to take any of the credit for it. I ask him what eventually happened to it, and he rather bashfully admits “I lost it” he says, “on Earth”. He thinks it slipped off while he removed some flying gloves. It seems a rather understated end to such an incredible story, but Mattingly himself is rather understated for a man of such achievement. I could have talked to him all night, but so could everyone else, so I give up my prime position for someone else to enjoy his company. As he headed off to bed he apologises that our conversation was cut short before commenting “what a neat bunch of people”.

The following day we’re gathered in the school hall awaiting his talk and I find myself wondering what he’ll say. I can’t imagine him focusing on his personal achievements or acting the star despite the fact that it’s his presence that’s brought people from far and wide – not just across the UK but from Europe and even the US.

He starts simple, with three questions for us:

- “Who here is interested in space?” – a room full of hands shoot up

- “Who is interested in human spaceflight?” – the same hands fly up once more

- “Who would like to go to space?” – I’m not sure about anyone else, but I raise both hands at this point.

I assume others followed the pattern for the final question because he congratulates us on our “graduation”. We’re ready for his talk.

The Apollo programme is almost as old as I am he says, “ancient history”. We laugh at this joke, but there is a slight sadness in the air as many of us realise that whilst “ancient” is a bit of an exaggeration, “history” is indeed what it is.

Mattingly talks us through some of the history that led to the Apollo programme – “one day we woke up to the sound of beeping from Sputnik” – the country was terrified he says. What do you do to recover from that? You put a man in space, and that’s what the Mercury programme was set to do, but then Russia put a man in space. “The panic was palpable” he recalls.

When Kennedy said that they would send people to the Moon and bring them safely back again by the end of the decade, that only gave them nine years. “The next nine years were total chaos” says Mattingly. They had to recruit a lot of new staff, but people wanted to work on the programme because they thought it was cool.

Mattingly, known as “TK”, uses the large model of a Saturn V that’s on the stage to describe the different stages of the rocket launch.

Finally pointing up at the command module perched at the top he says that when you see the real thing in a museum “it doesn’t look that small, ‘cos it’s empty.”

“Let me tell you, you really get to know people spending two weeks in that little bath tub”. This rare insight into his own experience is coupled with a sparkle in his eye as he remembers his flight.

Back to the rocket – “really a spectacular sight” he says of launch – “that sucker goes up!”

“Frank Borman thought he was commander when he got onboard, but realised within one second he couldn’t command anything – you can’t command that thrust”

Talking about his own flight on Apollo 16 he remembers thinking “we’re still goin’ up, that’s a good sign”.

He had heard about people getting sick in space and started to worry that the first thing he did in space might be to throw-up. As it happened as he got up out of his couch and the first thing he thought was “I’ve been here forever – it’s perfect!” There’s something so genuine about the way he says it – it’s not just a line he reels out at talks because it is what people want to hear – but full of emotion, wonder, and relief.

“You can entertain yourself for a day just throwing stuff” he says, but then adds that “the novelty of floating really wears off after two-and-a-half days with someone in your face all the time”.

Looking out of the window, he thought “this going to the Moon is really neat!” (I’ll say! just a bit!), “but I want to come back and see the Earth – it’s beautiful”.

We get a little more of Ken Mattingly at this point. He shares how as aviators, when you see a thunderstorm, you fly the other way, but when you’re flying over them in space you think “that’s really cute – little sparkling lights”.

“You never tire of looking at the Earth” he says before adding that “the Moon is not beautiful, but seeing Earth-rise over the Moon is beautiful”.

He moves on to talk about Apollo 13, the fateful mission that he was due to be part of, but due to a worry that he had been infected with German measles, was removed from at the last minute (well, 72 hours before it flew, to be exact).

“Apollo 13 was not a failure” he says confidently, “it was the only example of why we succeeded, that you could see”.

“There are moments that catch your attention and they don’t last long, but they are indelible” says Mattingly.

He explains how a couple of weeks before launch they had one last weekend when they could go home. When he got back to the Cape he found that one of the children at the picnic he’d been at had come down with German measles. If you’ve been exposed to measles before, then you’re okay, he says, “and what adult hasn’t been exposed?”

“Well, they found me.”

They took blood samples from him twice a day for testing. He says they took so much blood “I was afraid if they launched me I would be anaemic”.

Eventually they decided that they couldn’t take the risk with him. He couldn’t believe it. He references the film version of Apollo 13 “let me tell you – his portrayal of feeling sorry for self was terrible!” – implying that he felt much worse than even the film suggested.

He recalls sitting on the floor in Mission Control between the CapCom and the Flight Director because there was no space for him there.

He recalls sitting on the floor in Mission Control between the CapCom and the Flight Director because there was no space for him there.

During the flight the Apollo 13 crew were sending down pictures from the LEM. He was watching in the VIP area, and no one else was really around. Just him and one other guy – it wasn’t like the previous launches when those spaces had been bustling with people. The crew said goodnight and the other guy said to Mattingly “you look like you need a beer” before going off to get his briefcase. Then Mattingly heard a voice over the air to ground comms system and, in his words, “the whole world changed”.

The team were together in minutes and within two hours the parking lot was crowded. It was the middle of the night but there were heads in every office he said. There was no drill to practice this but people heard the news on the radio and came straight in to help – some of them didn’t go home for 4-5 days.

When an accident occurs they are trained not to get fooled by bad instrumentation; “it can lead you to do bad things”. When the Apollo 13 incident began their first thought was to check the instruments and they thought it was that, but then they heard a voice asking “when was the last time instrument failure made of cloud of stuff out the sides?”.

This was right about the time they were due to do a shift change from Glynn Lunney to Gene Krantz. They decided to split into teams – one to get them safe and one to get them home.

“Talk about confusion and pandemonium” says Mattingly, “everyone had an idea for someone else, but not for themselves”. According to him, Glynn Lunney found specific tasks for specific people and that was when the “machine starts to run”.

Having earlier admitted that he had done his best to “cheat Swigert out of SIM time”, Mattingly says that the future relies on simulations of unrealistic problems. They were criticised for doing them, but he remembered doing a Sim where they had used the LEM as a lifeboat. When they called up to the crew they were already doing the “LEM lifeboat” procedure. The command and service module was going to die in less than an hour.

The crew moved into the lunar module hotel – three in the space of two – but without electricity, it was good to have an extra body for heat.

There was frost inside. All the electronics were behind panels that were below freezing. They had not been qualified for those conditions.

They worked through options for getting the crew home. A direct return would use all the propellant that they could get their hands on and there was no room for error. Where would they land? They didn’t know.

If they went around the Moon with life support only, saving energy by shutting all computers down, would they be able to align? They decided to leave the relevant equipment off until the last minute, when they had some information to put into it to help them align.

If they did this, they would have an Atlantic landing, but all the recovery crews were in the Pacific. They found one more manoeuvre that would allow them to get to the Pacific – then it was lights out, and miserable cold.

All the contractors were ready to take calls about any of their equipment – not just the staff, but the head’s of the companies were answering the phone and ensuring NASA has all the information they needed about their equipment.

Mattingly recounts an incredible story about a vital piece of equipment – the inertial measurement unit (IMU) which measures the spacecraft’s velocity and orientation – that had never been tested outside of temperature limits. Would it work when they switched it back on? They had no test data because they never imagined it would have to work in such cold conditions.

A NASA contractor heard the news about the drop in temperature and the concern that equipment might not work. He called his boss to admit something he’d done wrong, and had previously covered up. When a snow storm hit and their factory had been closed due to the cold, the last thing he was meant to do before leaving was to take this piece of equipment from one building to another. He put it in his truck, but then forgot about it, leaving it out in the cold. Embarrassed by this mistake, he decided rather than owning up, he’d sneak it back in to the factory and leave it on the table it was meant to be on.

Knowing it was an important piece of equipment; he did go back and check with the testers that they hadn’t found anything unusual on their next text. They said “no”, so he could sleep at night.

When the Apollo 13 crisis was unfolding, he realised that his boo-boo might actually give them a useful data point, so he came forward and admitted to his boss what had happened – not only owning up to having done something wrong, but to covering it up as well.

That one data point said that it might work, and there was a great sense of relief says Mattingly.

“That kind of free communication brought them home” he says.

You have to remember that mid-20s was the average age of people in the Mission Control Centre. “Sometimes the social interactions were not always smooth – but everyone wanted success.”

And with that, Mattingly opens the floor to questions, but not before we gave him a standing ovation. I watched him as we did, at first relieved and smiling, and then again, that sign of the humble man he is, slightly uncomfortable with the level adoration focused on him.

Ken Mattingly seemed delighted to take questions – again, it was something that helped take the entire spotlight off him, and made him feel that the words he was sharing were genuinely those we wanted to hear. First up, given that he’d said floating round in space was boring with people in his face all the time – how did it feel when he was on his own?

“Wonderful!” he exclaims, without hesitation.

He then shares the story of how the original Apollo 13 crew had made a special tape with the three of them talking, and that they were going to play out in the LEM to make it sound like they were all in there. While the tape was playing he was going to refuse to answer any calls from mission control as they did so – to make it seem like all three of them were headed to the Moon! Obviously they never got to do that, which is a shame, but again makes me smile that these heroes all have a sense of humour.

“What was it like to ride two launch systems?” someone asks, “what’s the difference between Saturn V and Shuttle?

“Stark terror, and isn’t this cool” he says. “Really really different!”

A younger member of the audience asks what his favourite space food was… “I don’t think we’ve created that yet” he says “it’s not like eating at home”.

Finally he is asked how he feels about the “Spam in a can” accusation that test pilots levelled at the astronaut corps. “Test pilots made fun of the space programme” he says, adding that “pulling Gs is fun, but flying is zero G is more fun” in a characteristically diplomatic way.

It’s been a delight listening to Ken Mattingly, I only wish I’d had more one-on-one time with him – not only because he’s an Apollo astronaut (and why wouldn’t you want one-on-one time with any of them?) but because I feel that he (and I) would be more comfortable in that setting.

Ken Mattingly is a humble, wonderful, astronaut, who was lucky enough to look out of the window, and smart enough to realise that it was the work of thousands of others that enabled him to do so. What a gent.

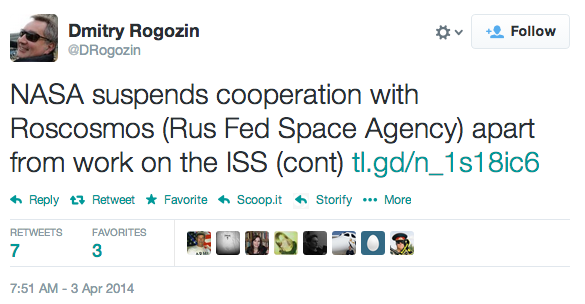

Today I was alerted via Twitter to the news that “all NASA contacts with Russian Government representatives are suspended, unless the activity has been specifically excepted”. This is as a result of the ongoing situation in Ukraine in relation to the sovereignty of the nation. My initial concern was what this would mean for operation of the International Space Station whose major partners are the US and Russia.

A leaked memo clarifies this concern, stating that “Operational International Space Station activities have been excepted”. The memo, apparently send yesterday by Michael F. O’Brien, Associate Administrator for International and Interagency Relations was leaked to spaceref.com (where you can read the full text).

Dmitry Rogozin, Deputy Prime Minister of Russia turned to Twitter to play down the move, stating that “apart from over the ISS we didn’t cooperate with NASA anyway”.

So is this something that we need to be concerned about?

Personally I think that the answer is yes. After years of being sworn enemies, the US and Russia found ways to work together in space, first via the Apollo-Soyuz Test Project and now with the incredible symbol of international co-operation that is the International Space Station (ISS). NASA Administrator Charles Bolden was quoted as saying that relations with the Russians were “normal” just a few weeks ago during a budget teleconference, adding “I think people lose track of the fact that we have occupied the International Space Station now for 13 consecutive years uninterrupted, and that has been through multiple international crises”.

It seems a shame therefore that this relationship, crucial to the success of the ISS should be put at risk by political forces. Whilst the ISS operations are excepted from the suspension, it hardly sends out a great message of co-operation. If I were an American politician I think I would be wary of rocking that boat at the moment, especially since the US is currently entirely reliant on getting its astronauts safely to and from the space station since the retirement of the shuttle. It is one thing for them to want to appear to be playing “hard ball”, but have they considered the potential repercussions? What if Russia decides it won’t honour future contracts to fly US astronauts to the ISS? It’s unlikely, but there is the potential that the US astronaut onboard the station could find himself with no way of getting back to Earth.

I can’t imagine that the astronauts and cosmonauts in space (nor the ground teams supporting them) would allow earthly politics to affect their life on station too much – after all they rely on one another to stay alive and keep the multi-billion dollar station functioning. But it doesn’t stop this situation from troubling me.

The International Space Station has been hailed as the most complex international engineering project in history. I hope that all the work, money and inspiration doesn’t get muddied by politics while its in its prime.

Update: NASA statement released

Statement regarding suspension of some NASA activities with Russian Government representatives:

“Given Russia’s ongoing violation of Ukraine’s sovereignty and territorial integrity, NASA is suspending the majority of its ongoing engagements with the Russian Federation. NASA and Roscosmos will, however, continue to work together to maintain safe and continuous operation of the International Space Station. NASA is laser focused on a plan to return human spaceflight launches to American soil, and end our reliance on Russia to get into space. This has been a top priority of the Obama Administration’s for the past five years, and had our plan been fully funded, we would have returned American human spaceflight launches – and the jobs they support – back to the United States next year. With the reduced level of funding approved by Congress, we’re now looking at launching from U.S. soil in 2017. The choice here is between fully funding the plan to bring space launches back to America or continuing to send millions of dollars to the Russians. It’s that simple. The Obama Administration chooses to invest in America – and we are hopeful that Congress will do the same.”

Update: Comments from Charles Bolden

Tweets from Marcia Smith of SpacePolicyOnline.com report the following comments were made by Charles Bolden at a meeting in Washington this morning (though I’m so far unable to locate a transcript of what was said):

Bolden to ASEB/SSB re Russia: I tell my ppl — unless I tell you otherwise, don’t stop doing what you’re doing.

— Marcia Smith (@SpcPlcyOnline) April 3, 2014

Bolden sez he talked to Roscosmos Direstor Ostapenko this am (who’s in Kourou for Soyuz lnch) and both agree ISS shld be outside of politics

— Marcia Smith (@SpcPlcyOnline) April 3, 2014

Opinion by .

Three years ago today, I saw something magnificent, something awe-inspiring, something powerful, something scary, something that made me shake (in more ways than one), something historical, and something I’d waited 115 days for.

Space Shuttle Discovery launched from pad 39A, Kennedy Space Centre, Cape Canaveral, for the very last time.

It was an emotional experience, not least because it was the first time I’d seen a space shuttle, in all her majesty, lifting gracefully off the planet in a blaze of fire and light. And not just because I knew the husband of one of those astronauts, one of those people, being rocketed through the atmosphere. Not even because I’d put my life on hold and waited, waited, waited, for that moment, but because of a combination of all those things, and the most amazing bunch of people that I could ever have wished to share it with.

You may have seen me refer to myself as the “Space Nomad” and wondered what the heck that is all about. It’s about Diva Discovery, NASA Tweet-up, and an incredible family of friends that were thrown together but then stuck together. I tell the story often, to anyone who’ll listen really… it goes like this:

I was selected to see one of the final shuttle launches, as part of a NASA Tweet-up. We would be able to watch STS-133 launch from the closest place anyone (except the emergency crews and the actual space shuttle crew) could be. 3.1 miles away at the KSC press site.

I packed my bags and off I went. Hotels were too expensive so I’d gathered a few people on an email list and we decided to share a house, and then another house, and another… five shared houses later we were ready to go. I had no idea who these people were, but they liked space, so they must be cool – right?

By the time I stepped of my plane from London, the launch date had already slipped back a day. But that was no problem; it gave us a bit more time to get to know each other before the big day – and to have a Halloween party.

There were further slips, it was going to launch on Friday. Some people already had to leave, but I’d booked to be away for ten days, just in case.

Friday came, our insider contacts sent us pre-dawn text messages confirming Discovery was being fuelled up. Things were good. This group of strangers had become friends, and today we were going to have the experience of our lives, watching a shuttle launch.

My dream team – DJ Flux and Nathan Bergey – jumped in the car. We took it in turns choosing the right dramatic music as we got closer and closer to KSC. Just as we parked up at the press site my phone beeped, I had an immediate sinking feeling as I realised no-one had my US number, except… oh.

“Scrub.”

That one word, unconfirmed to us at the time, took us from nervous elation to a strange, heavy, lost feeling. Uncomprehending, we hugged one another as tears, somewhat unexpectedly welled up.

The next launch window was in two week’s time, but I had to fly home by then and couldn’t afford to fly back again. I had to fly home… didn’t I?

The moment I decided I couldn’t afford not to see the launch, that you only regret what you don’t do, that I’d come this far and made these friends and and.., that was the time I became Space Nomad. I changed my ticket and went to sleep on a friend’s floor in California for a couple of weeks, fully intending to fly back for the launch a fortnight later, but…

..the problem was worse than they thought. It would be another fortnight until they could attempt a launch. I reached out to Twitter, asking what I should do next. Someone suggested Houston, so Houston it was. I stayed with an incredibly wonderful woman called Becca. We’d met a year before, and she worked in Mission Control (yes, actual Mission Control), she took me in and invited me to Thanksgiving dinner. It was an incredible act of kindness that I’ll never forget.

The two weeks were almost up, time to fly back to Florida for Discovery’s launch, or so I thought, but as was beginning to become a habit, “Diva” Discovery wasn’t ready to go yet.

I have the cut the long story short, else I’d be reminiscing over months of travelling, sleeping on floors and in spare rooms, visiting space centres and spacetweeps all round the US and having the most amazing adventure. I got to know Chris Shaffer, Flying Jenny, Tiff and Dave. I watched the first SpaceX launch of a Dragon capsule (and secret cheese payload). I was introduced to “My drunk kitchen” and “Baby monkey”. I flew a shuttle simulator. I baked Christmas cookies in a log cabin. I discovered Portland. I attended (and loved) my first SpaceUP. I giggled with Cariann (and made her miss a flight). I shared a “Katy Perry day” and I visited SpaceX. I saw the Hollywood sign. I made new friends and new family. And then I finally went back to Florida for the launch.

I packed for ten days, I stayed for four-and-a-half months (don’t panic, I had the right visa), but I had to see that shuttle launch. I stood and I watched as the iconic form of the space shuttle raised herself off the pad and on her final space adventure. I clapped and whooped and felt part of something so special because I was surrounded by these great people who all knew just how special it was too.

We quietened down as the low rumble reached us, getting louder and louder and LOUDER and LOUDER. We felt the power of that rocket shake the ground and shake right through us and we never took our eyes of her. Soaring above us we cheered again as the solid rocket boosters separated. We had nothing to do with her success, but we were like proud parents waving her off.

I turned around and Karen James was behind me. She knew Mike Barrett, one of the astronauts on board. I’d never really thought about what it would be like to know someone on top of a shedload of rocket fuel until Paolo Nespoli, an astronaut I’d befriended, launched to the ISS on a Soyuz rocket part the way through my space nomad adventure. It completely changed my perspective. No longer was it all about cool rockets, cool science and smoke and noise and fire and power. No longer were astronauts invincible superheroes who don’t really exist. They were people, friends, and Karen’s friend had be strapped into the thing that just made our camera shutters go wild and our rib cages shake. I’d heard her cheering and shouting throughout the launch, but now the shuttle was out of sight, I knew the focus for all that welled up emotion was also out of reach. I turned and hugged her. It was special. I had only seen Paolo’s launch via a webstream and I was a shivering wreck, I took a guess at how Karen was feeling. I think I guessed right.

We were all there, focussed on that one moment, together. This great group of people, who had once been strangers, are now forever connected by our shared memory of that day. Today, three years on, I’m thinking of you all and remembering it like it was yesterday. I love that people have tagged me in photos and memories, said hello in tweets and kept the 133 spirit alive.

You’re a special bunch, she was a special shuttle, and that was a very special adventure.

SpaceNomad TweetUp by .

It’s like this:

I would LOVE the UK to have a human spaceflight programme. I would LOVE the UK to lead the way in space exploration. I would LOVE for people around the world to look at our country and see that we are investing in science, technology and inspiring a new generation of engineers. So why am I not sold on SKYLON?

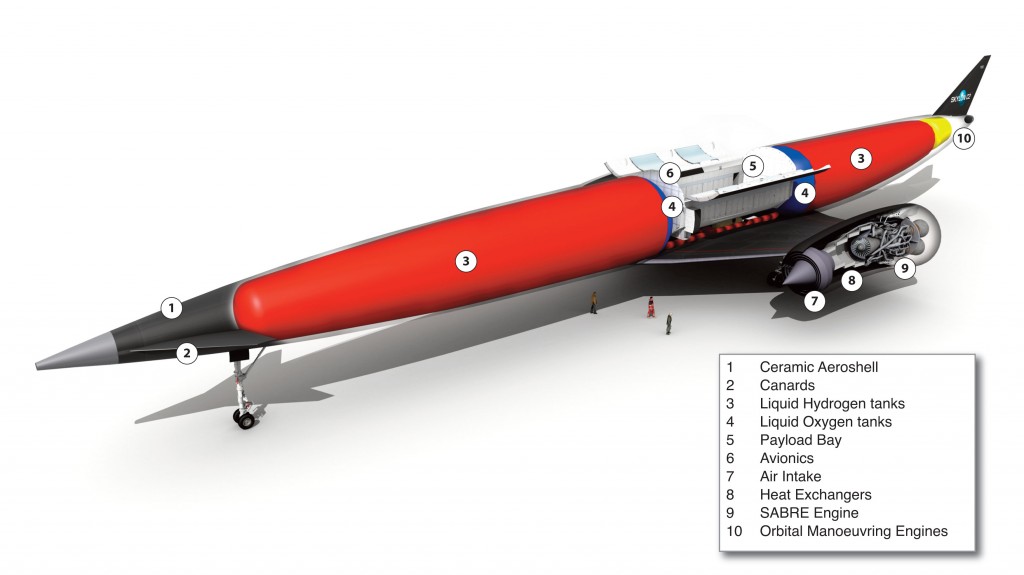

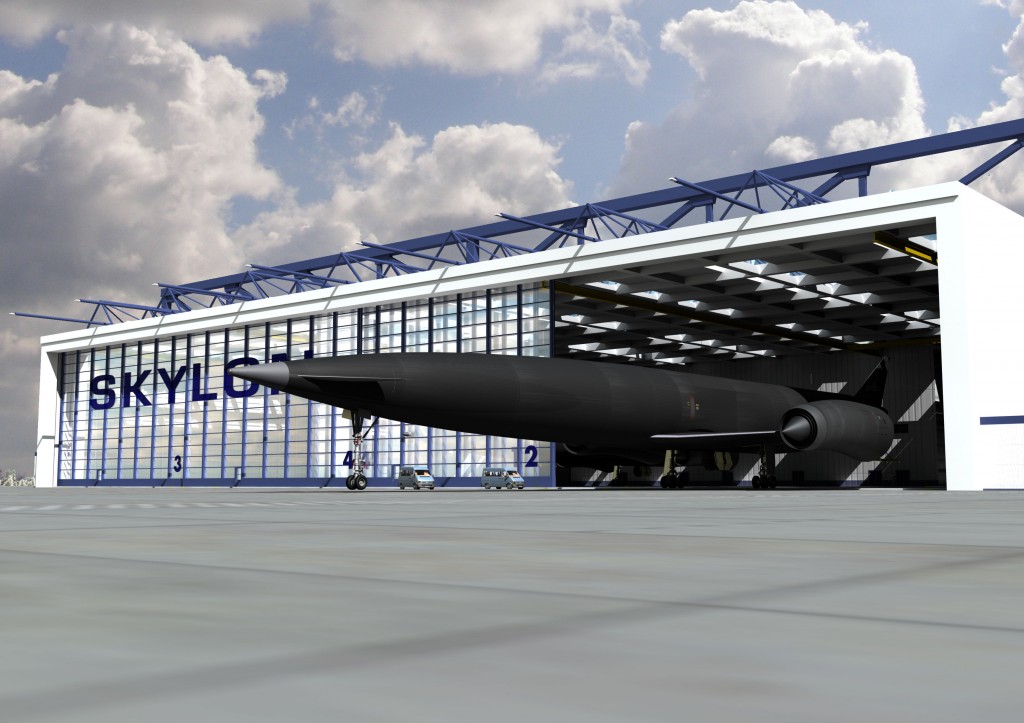

SKYLON could be the answer – a space plane that can go from runway to orbit and land back on a runway again. A fully reusable vehicle which promises cheaper launch costs and a more reliable launch system, and it’s being developed here in the UK. The air-breathing SABRE engines that Reaction Engines are developing are the key to this, and according to Mark Hempsell, who’s worked for Reaction Engines for many years, the feeling inside the project is that it’s “achingly close to being realised”.

Image Credit: Reaction Engines

At a recent talk at the British Interplanetary Society, Hempsell, (who is leaving Reaction Engines to work for his own company, Hempsell Aeronautics) said we’re at an “absolutely unique point in astronautical history”. He went on to explain how SKYLON’s 4.8x13m payload bay could take 15 tonnes to Low Earth Orbit (300km) and because it’s reusable it will bring down the cost of reaching space. Cost being the fundamental thing holding back astronautics he explained.

He went through various factors, looking at the short- and long-term hopes for SKYLON. For example, in the short-term, he said that SKYLON will be fully commercial at lower-than-current launch costs (i.e. no tax-payer subsidy required to make up the launch cost). In the long term they are looking at around $10 million per launch.

Hempsell said that SKYLON will be more reliable than current launches, and since it has the option of aborting a mission and returning to Earth if there is a failure, he reckons there would be just a 1 in 20,000 chance of not getting your satellite successfully in orbit, or safely back to Earth in case of a problem. In the long-term they are looking at having reliability levels that match those of aircraft.

Availability is another key selling point. In the short-term, SKYLON could be available in a matter of months, and in the long-term they are hoping for it to be available in hours (if required – not as standard!).

So which market are they aiming for with SKYLON?

In the short-term Hempsell expects it to be a simple replacement for expendable satellite launchers, but the long-term ambitions are much grander. He says it’s a game changer, disruptive technology that could lead to a new age of space exploration – allowing people to realise those old dreams of people living in space.

The optimism continued as Hempsell explained that SKYLON can meet the requirements of the next generation European launcher. He reckons they can capture the market that ESA has. “This is a perfect match for what ESA thinks it will be doing until 2050” he says, adding that although ESA has no human spaceflight requirement at this stage, SKYLON will be sold to people who do, in the 2020s.

He claims that SKYLON could fly to the ISS with 11.5 tonnes of payload (or 10.5 tonnes if you allow for an attachment interface – which is rather crucial if you think about it!).With a crew/cargo combination you’d be looking at being able to send up an exchange crew of three to four people, plus around two tonnes of cargo.

They are also looking at a “personnel and logistics module” that could sit in the payload bay and take around 7.8 tonnes, including a crew, consumables and around 24 passengers into space. They expect something like that to be available when they’re ready to launch.

Here’s a (somewhat outdated) video explaining the module:

SKYLON Personnel & Logistics Module from Reaction Engines Ltd on Vimeo.

So that’s the satellite launch and space tourism markets covered, what about its potential for furthering exploration? “Project Troy” was a study looking at whether SKYLON (the old version, rather than new D mark) could be useful for a Mars mission. The study “proved” that SKYLON can launch a manned mission to Mars. They looked at building spacecraft in LEO and boosting them to Mars with Hydrogen and Oxygen fuelled stages. It suggests a fleet of three craft, each with six astronauts. Fascinating. Must find out more.

Project Troy was carried out to ensure that SKYLON is future-proofed says Hempsell. Thinking ahead to possible future scenarios is a smart move, though whether I would agree it is possible to “prove” a vehicle that as yet doesn’t exist (and airframe design is not finalised) is capable of a Mars mission, I’m not sure. “SKYLON will not be a block to realising customers’ dreams” say Hempsell. It’s a bold claim.

He talked us through the concept design of the “Fluyt” stage, which was worked on by Simon Feast. This could deliver 15 tonnes to GEO, and around 12 tonnes to lunar orbit apparently.

They also looked at a post-ISS scenario, in which they envision 14 space stations situated from LEO to the lunar surface, with 104 people in space, including a space hotel.

With one operational SKYLON flying twice a week, he told us it would be possible to build a space station in LEO in just 6 weeks, and a GEO/Lunar station in 18 weeks. With two SKYLONs you could build the whole 14 station infrastructure in less than three and a half years!

It’s exciting stuff. Imagine that! – building a space station in just six weeks – with a UK space vehicle! That would certainly put us on the map as a serious space-faring nation.

So why am I not rejoicing? Why am I not leaping about and extolling the virtues of this vehicle? If it can do all of the above it really would be a game changer. What’s my problem? (Apart from the fact I think it looks like an evil whale harpoon.)

Image credit: Reaction Engines

My problem is that it doesn’t actually exist.

SKYLON, the thing that we keep hearing about, is not the main focus for Reaction Engines. In fact, they are not even going to create the airframe for it, someone else will. The idea for producing SKYLON is to create a customer for the engines that Reaction Engines are making. Their air-breathing engines might well be game-changing, but we’re a long way away from all the things that Hempsell was so excited to talk about.

He himself admits that the devil is in the details. He mentions an issue with docking mechanisms – they don’t want to change the one that is designed for Skylon, but that would mean satellites would have to add a special SKYLON interface mechanism in order to work with the vehicle. This would add an extra 5-10kg to the satellite says Hempsell. It might not sound much, but I’m pretty sure it’s no simple undertaking.

For crew/cargo delivery to the ISS to be fully effective, you would require a docking system with a hatch big enough to get equipment racks through. Apparently the current ISS hatches can’t do this and you have to go through berthing modules. (Correct me if this is wrong, I’m just reporting what he said).

His solution to all this is to develop a Universal Space Interface Standard (USIS) that could be used for all applications, by all users, all the time. It sounds like a perfectly logical idea, but when you note that the ISS partners spent years developing their own international docking system standard (IDSS) and then the US decided not to include it on Orion, and Russia isn’t going to use it either, you realise that it’s (unsurprisingly) a bit more complicated than just having a good idea.

The IDSS is apparently too heavy, too small, too expensive, so there is lots of potential for something light, cheap and useful to all. This is undoubtedly true, but if major space-faring nations, working together, with a vested interest in making something work (i.e. improving access to ISS and future co-operations) can’t do it, that has to be a bit of a warning flag, no?

As he’s speaking, I note that Hempsell uses “trick”, “little trick” and “nice little trick” a few too many times for me to take all he is saying without a pinch of salt.

The talk was entitled “The Future of SKYLON”, but by the end of it I’m left with more questions than answers. Hempsell has spun a seductive tale of the future of exploration, the Moon, Mars, SKYLON, but the basic questions still hang in the air.

We’ve heard so much about the incredible stuff SKYLON“could” do, but little about the details of getting it to a point where it exists, and this is reflected in the questions at the end.

“How long, realistically, will it be until the first launch or prototype?” asks an audience member. “If money were no object, around 2020” replies Hempsell, but he thinks 2022 is more likely since politics, money and partners will limit things (though not the technology).

What about funding? Well the funding so far is for Reaction Engines, not SKYLON. The money they have for SKYLON is not huge admits Hempsell, they need more. For the SABRE engine they have some kick-off funding from ESA (€8m), £60m from government and the rest is apparently private (but that’s commercially sensitive information so he can’t say more).

There are questions about how the vehicle will be certified for human flight (rules currently being defined by the CAA, in conjunction with international agencies says Hempsell) and my question, about reliability.

It strikes me that making reliability comparisons with companies like SpaceX, is not entirely fair. How can you compare the reliability of a vehicle that exists (and is constantly evolving and improving) with one that doesn’t?

I could tell you that my rocket is going to be 100% reliable. Beat that.

I can say that, and it’s meaningless, because my rocket doesn’t exist and so there is no way of testing the assertion. How is this any different?

Hempsell assures me they’ve done lots of work to back up their assertions and says that the difference between them and SpaceX is that their vehicle will be fully reusable, thus increasing reliability. I can’t help thinking that since SpaceX are already building and flying rockets, and moving closer to a reusable system themselves, that this still a little unfair.

Remember, even if money were no object they don’t think that they will have a vehicle until 2020, that’s plenty of time for SpaceX to keep improving their systems and reliability. They are not exactly known for hanging around with things after all.

“What about the shuttle?” I ask, “that was meant to be reusable but budget cuts changed the design – couldn’t the same thing happen to SKYLON?”. Hempsell focuses his answer on the fact that the shuttle wasn’t really reusable and had many expendable parts. Those were the bits that failed, the bits that had were new for each flight, rather than having been tested in a flight scenario first. This wouldn’t be the case with Skylon which is going to be fully reusable he asserts.

I’m still doubtful; after all, the greatest of plans can be crushed by politics and budgets. What’s to say that similar compromises won’t have to be made to get SKYLON into existence? “When you see expendable bits on SKYLON, that’s when you know there’s a problem” says Hempsell.

Indeed.

But I think that there already is a problem, and that’s the unrealistic assumptions being made about everything from the financing, to the ease of persuading existing space powers to adopt new interfaces. The throwaway comment he made about adding another runway to Heathrow shows little appreciation of practicalities.

By assuming, indeed relying, on the best case scenario in many complex situations, I think that they are setting themselves up for disappointment. Much as I’d love to believe that SKYLON is the future of UK space exploration, I think it would be unwise to pin my hopes on it until there is more concrete proof that finances are in place for it to be built, let alone live up to our hopes and dreams.

Perhaps I’m too much of a cynic, but I’m always open to changing my mind. Please add your comments to this post – I’d love to know what you think.