Nov

6

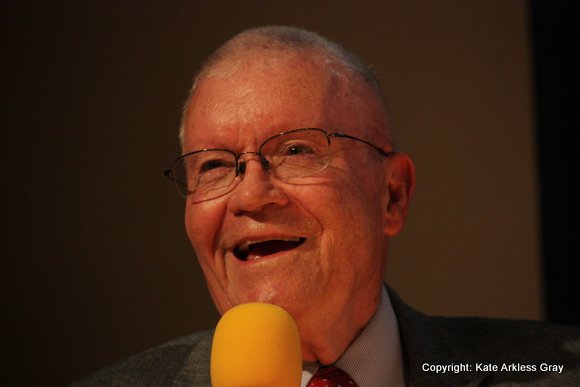

You’ve seen the film, you know the dramatic story, but meeting one of the members of the ill-fated Apollo 13 mission is something else. Ken Willoughby and the Space Lectures team secured Apollo 13 Lunar Module Pilot Fred Haise as their guest of honour in Pontefract for the final weekend of October. We all came away knowing something new – though not perhaps what we had expected…

“My name is Fred Haise, I’m a NASA astronaut” begins Haise, “I flew Apollo 13 a while back”.

“My name is Fred Haise, I’m a NASA astronaut” begins Haise, “I flew Apollo 13 a while back”.

Thus begins my chat with the understated Fred Haise. “I wanted to be a journalist” he tells me, “I studied journalism for two years at junior college and freelanced for AP – they paid 75 cents a line”.

It was the outbreak of the Korean War that changed his course as he joined the naval aviation cadet programme. “I’d not been interested in flying, I’d never flown, but I loved flying” he says, “that made a right turn in my career”.

There’s something very matter of fact about the way he describes joining the astronaut corps. “I’d been working at NASA before, so for me it was just another transfer from one NASA centre to another one”.

“I didn’t think of myself as a particularly renown person at the time, I was just a test pilot” he says.

There’s that word again “just”. It’s a word he seems to use a lot when talking about himself. I can’t tell whether that’s because he’s uncomfortable with the level of recognition and awe he now commands, or that it’s a reflection of his view that he was “just” a test pilot, getting the job done.

That’s not to say he’s blasé about it, “I feel very fortunate to have stumbled into this line of work” he says.

A few minutes into his lecture at the Carlton Community High School, Haise mutters that immortal phrase: “We’ve had a problem”. This time however, it’s just an issue with the microphone he’s using to deliver his talk – we share a moment of laughter as they disentangle him from the wires of the headset and give him a hand-held mic instead.

A few minutes into his lecture at the Carlton Community High School, Haise mutters that immortal phrase: “We’ve had a problem”. This time however, it’s just an issue with the microphone he’s using to deliver his talk – we share a moment of laughter as they disentangle him from the wires of the headset and give him a hand-held mic instead.

“There was no book for this set of problems” says Haise, referring to the multiple failures caused by the oxygen tank explosion on Apollo 13. Despite many hours training in the simulators at both Johnson and Kennedy Space Centres, the escalating string of issues they had to deal with was something new.

In fact, one of the reasons they’d not planned for it was that the problem was so serious an issue that crew were lucky to have survived it at all.

“We kinda gave them a problem” he says, “we were still sitting there breathing”.

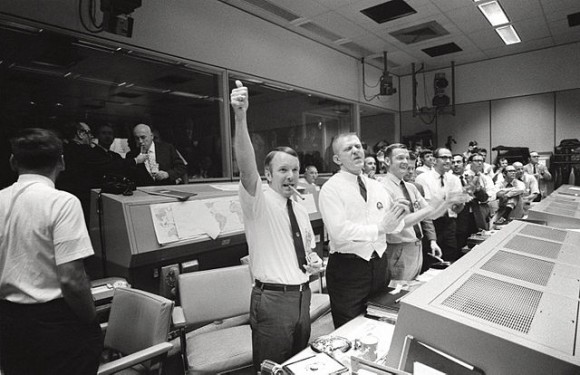

The mission control team had their work cut out. Although the initial aim of the mission, a Moon landing at Fra Mauro, was lost, the crew were not – and that meant they had to work round the clock to return them safely to the Earth.

It was not like a car swerving off the road though, says Haise, in fact it took Mission Control 18 minutes to come to the same conclusion that the crew had come to, that the oxygen tank was lost. “Sy Liebergot got a lot of heat for that” he says, “for 18 minutes they thought it was an instrumentation problem”.

The crew had been filming for a TV show two days into the mission, finding things to show people that the other missions hadn’t already covered, giving a little tour of the vehicle and enjoying the effects of microgravity – “it’s kinda euphoric” he says.

TV transmission from the Apollo 13 crew moments before the accident that crippled the mission. Fred Haise can be seen on the large screen at the upper right.

It was at the end of the filming that they had the problem. “It ended up being a very long day” he says earnestly.

“Initially I was still in the landing craft, putting away stuff” he explains. “By the time I drifted up the tunnel to the right seat – that had all the electrics – all three meters were down at the bottom for tank two”.

“I just had a sick feeling in my stomach. I knew that we had lost the landing. Without referencing mission rules or the books I knew that was an abort, to lose one of the tanks.”

Haise had trained as back-up for both Apollo 8 and Apollo 11, but this was his first flight. “Here I had my chance, and it was gone in an instant”

This last line, delivered with an almost imperceptible tinge of sadness, a little quieter than the others, is the closest I feel I’ll get to the truth of the disappointment. Haise is a military pilot, a test pilot, a “stiff upper lip think of the mission” pilot. There’s not room for emotion when you’re thinking of the next thing that could kill you, and while he talks at length about the technical details, he doesn’t give much away about the emotion behind the experience.

This last line, delivered with an almost imperceptible tinge of sadness, a little quieter than the others, is the closest I feel I’ll get to the truth of the disappointment. Haise is a military pilot, a test pilot, a “stiff upper lip think of the mission” pilot. There’s not room for emotion when you’re thinking of the next thing that could kill you, and while he talks at length about the technical details, he doesn’t give much away about the emotion behind the experience.

I wonder if he’ll say more, but we’re back onto the timeline of what happened, how it panned out and who knew what, when.

Haise is keen to point out the sheer number of people who worked the problem and got the crew safely home. “One of my main complaints to Ron Howard about the film (Apollo 13) was that it didn’t show the number of people involved” he says, though he admits Howard pointed out he had neither the budget for so many actors, nor the time to introduce them all as characters in his blockbuster film. Fair point.

“A few years ago I listened to the back room loops” says Haise, referring to recordings not of the space to ground communications, but those containing the discussions in the “back rooms” – the rooms of experts that supported those people in the main Mission Control centre.

“We were desperately trying to isolate the leak in the second oxygen tank” he explains, “we would have aborted even without that, but it wouldn’t have been as bad as it was”.

Listening to the tapes, decades after the incident itself, he describes hearing the voices of people he knew – hearing from the inflection in their voices that they knew they’d lost it, and they were losing hope. A new Mission Control team came on and they realised they had to shutdown the command module, and fast. “We were eating into our entry batteries”.

There was a change in the voices, some hope, but now they had a new problem to deal with. The command module was never meant to be shutdown during flight so there was no manual for the procedure. Despite that the team worked out what to do and they worked through the shutdown sequence and managed to do it safely.

“When I listened to the tapes, it really made me want to applaud” he says, with obvious admiration for the commitment and skill of those involved.

Commander Jim Lovell tasked Haise with calculating the consumables required, assuming a return time of around 150 hours. Haise recalls that they were running out of water, but he thought that they were okay on electrical power, and plenty okay on oxygen – especially with the two suit tanks that were no longer required for Moon walks. He didn’t think of carbon dioxide as a consumable and missed that from the calculations – though of course it was the build up of carbon dioxide that caused another big problem for them, requiring them to create a makeshift CO2 scrubber.

Commander Jim Lovell tasked Haise with calculating the consumables required, assuming a return time of around 150 hours. Haise recalls that they were running out of water, but he thought that they were okay on electrical power, and plenty okay on oxygen – especially with the two suit tanks that were no longer required for Moon walks. He didn’t think of carbon dioxide as a consumable and missed that from the calculations – though of course it was the build up of carbon dioxide that caused another big problem for them, requiring them to create a makeshift CO2 scrubber.

“It went real cold so we stayed in the LM(Lunar Module)” says Haise, “we didn’t go into the ‘icebox upstairs’ as we called it”, talking of the shutdown command module.

The crew were no longer able to heat their food and soon gave up on trying to eat anything powdered. “We ate cookie cubes, bread cubes and peanuts from a little larder of snacks” he explains.

Cooling vapour being released from the lander (not usually present when returning from the Moon) had pushed them slightly off course – enough that the craft could have “bounced” off the atmosphere and been lost forever. They had to correct for this, without the computer and without being navigate using the stars since there was still too much debris glistening around them. Instead they used the Earth’s terminator – the line where the light of day and shadow of night meet – for guidance.

“We did two short burns, one of 18 seconds, one of 21 seconds. One with the descent engine and the other with the four RCS (Reaction Control System) engines” says Haise, explaining that unlike the way the film presents it, they didn’t swing around all over the place – that was just put in for dramatic effect.

“We did not move more than one degree in any deviation in any axis” he states firmly. Jim Lovell controlled the yaw of the spacecraft, while Haise controlled their pitch. He lightens his tone to mention “the biggest deviation was in Jim’s axis”, adding a wry smile.

Despite all the issues, not only did the crew get back safely, but their splashdown was one of the most accurate of the whole Apollo programme. “Only Apollo 10 did better”.

It’s an impressive feat, and the crew’s safe return deserved some celebration, but unlike other missions there was no splashdown party when the crew landed. Those in Mission Control were too tired, some of them having never left once they were called in, choosing instead to lie down in corridors to nap when they knew they needed to. They celebrated by getting some sleep.

Haise tells us the Apollo 13 crew are unique in that they were allowed to go to their own splashdown party, which was held two weeks later. What a party that must have been!

He survived Apollo 13, but sadly the next mission he was slated for, Apollo 19, did not survive financial cuts. His chance at the Moon really had been lost in an instant.

Haise is asked about his role as CapCom for Apollo 14′s Moonwalk – which had inherited Apollo 13′s landing site – was that bittersweet for him?

“Bittersweet?” he says before a pause, “Every time someone landed on the Moon it was bittersweet – not just 14.”

But he’s lucky to be alive – and Apollo 13 was not his only narrow escape. Continuing with flying he had an engine fail at around 300ft on the set of the Pearl Harbour film “Tora! Tora! Tora!”. Attempting to land in what he thought was a dirt field, he found the start of a housing project, filled with ditches. Having caught a wheel in a ditch, he was in trouble. Trouble that left him with second degree burns over 65% of his body.

After months of treatment, and many more to get back to flight status, Haise was ready to take to the skies again. In 1976 he joined one of two duos tasked with carrying out the approach and landing tests for the latest space vehicle, the space shuttle.

Sitting up in the shuttle cockpit atop a 747 plane that took them up to around 30,000ft for the test was “like a magic carpet” he says. “You couldn’t see the 747 at all.”

Haise takes a detour from speaking of his direct experiences at this point. “Apollo was a very unique programme” he says. “Lots of things all lined up at the right time to allow it to be properly supported and funded.”

“But why did it happen then and not since?”, he asks. His answer comes in three parts – firstly, there was a threat. The Soviets, with Sputnik and Gagarin, made the US feel threatened.

Secondly, John F Kennedy wanted a way to declare the technological capability of the US. Various options were suggested, but the Apollo programme happened to tick the right boxes. “I don’t think, personally, that he was a space fan” says Haise.

Finally, for something like Apollo to become reality, there cannot be something else drawing on your national budget, like a war.

“You can dream about doing something, but you better have the technology to pull it off” he says.

Haise shares his views on the way the space shuttle programme was squeezed and the issues that caused. “Content got taken out of the programme” he says, “They cut the second Enterprise (test vehicle) and moved OV-99 from being a test vehicle to a flight vehicle”. (This orbiter later became more commonly known as Challenger.)

Haise shares his views on the way the space shuttle programme was squeezed and the issues that caused. “Content got taken out of the programme” he says, “They cut the second Enterprise (test vehicle) and moved OV-99 from being a test vehicle to a flight vehicle”. (This orbiter later became more commonly known as Challenger.)

The whole shuttle programme was delayed, with the first orbital launch coming two years after its original scheduled date. This is one of the reasons Haise didn’t make a return to space on the shuttle.

Haise also mentions the “worrisome” nature of a change in administration from Nixon to Carter. Carter cancelled the B1 bomber project just at the time they were conducting the approach and landing tests for the shuttle, “it was pretty obvious that space was not in his top ten priorities” he says.

“That morning when we climbed into Enterprise there were Polaroids stuck on the steps at the top” says Haise. The photos showed their colleagues dressed in blue suits (flight suits), wearing hats and masks, pretending to be Haise and his crewmate

Gordon Fullerton. They were sat posing on a street sweeper with the message: “If you foul this up, this will be your next job!”, written on the photos.

It may have just been a prank, but it reflected everyone’s worst fears. Had they crashed Enterprise it would have set the programme back by at least two years, says Haise. Thankfully that didn’t happen and thirty years of shuttle flights ensued.

“I just feel very fortunate with my total career” says Haise.

“Magically, luckily, I got into flying. I was going to be a journalist – like Kate here, making notes” he says picking me out of the crowd and causing me to feel simultaneously self-conscious, and proud at having been name-checked by an Apollo astronaut.

“Magically, luckily, I got into flying. I was going to be a journalist – like Kate here, making notes” he says picking me out of the crowd and causing me to feel simultaneously self-conscious, and proud at having been name-checked by an Apollo astronaut.

Haise closes his talk by saying “I arrived at the right time, with the right experience and the right background for Apollo”.

“Today they are people with the same credentials, but no programme to go into” he adds, slightly ruefully. “I feel very lucky to have had the chance”.

The room fills with applause and he is given a standing ovation. At 81 later this month, Haise is in fine form, and despite talking late into the evening the night before, he patiently signs autographs without a flicker of tiredness.

I feel very lucky to have met him. Journalism’s loss was definitely NASA’s gain.