Credit: NASA

So you wanna land on Mars?

Yeah – sounds good. Got any tips?

Well first off: Good luck!

What do you mean “good luck”? – we’re talking about rocket science aren’t we?

Yeah, and if you spend any time with rocket scientists you’re going to hear someone say “space is hard”. That’s because it is. In fact 50% of missions that intended to land on Mars have resulted in failure.

That means 50% succeeded though, right?

You’re right! Okay, so you still wanna give it a go? Getting things to Mars is hard enough, but ensuring you don’t then just smash them straight into the planet requires another level of expertise. You need a way to slow them down.

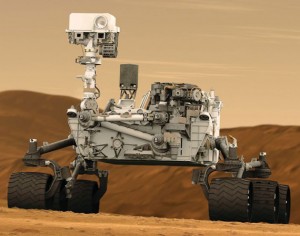

Let’s look at the current state of play. We’re still using parachute technology from the 1970s. The Viking landers used it back in 1976, and most recently Mars Science Laboratory used it, together with sky cranes and other pyrotechnic gizmos to land Curiosity on the red planet.

So what’s the problem? If it ain’t broke, don’t fix it…

Mars Curiosity Rover Credit: NASA

Sort of. The issue is that the Viking-era parachutes have limitations in terms of the amount of mass they can be used to land. MSL (Curiosity) has a mass of around a tonne, but if we want to explore further, take more instruments, and eventually take people to Mars, you’ll need to be able to transport much more than a small 4×4-sized rover like Curiosity.

Our current landing capability on Mars is about 1.5 tonnes, so one of the first steps on the technology development path to Mars is working out how to land larger masses.

You mean (to coin a phrase from Jaws) “we’re gonna need a bigger boat”?

Exactly – though it’ll be less boat, more space ship! If you want to land people on Mars you will have to send them up with the supplies that they need to survive. Food, water, air, habitats, rovers, tools and medical supplies will all have to be sent from Earth. You’ll also want an ascent vehicle so that you can get back off the surface to come home again.

How much cargo are we talking here?

Well NASA’s Bill Gerstenmaier, who looks after Human Exploration and Operations, reckons you’re looking at needing around 15-20 tonnes of cargo for a human mission to Mars. Bearing in mind the biggest thing we’ve landed on the red planet so far was Curiosity, at less than a tonne, that would require a big jump up from our current capability.

Well you use rockets to get you there, can’t you use rockets to slow you down too?

Slowing things down from supersonic speeds would take a lot of rocket fuel, but when every kilo counts – and costs – you want to minimise the mass you are launching. In fact to slow your vehicle down with rockets would require about the same amount of fuel as you needed to launch it, which makes it pretty unviable.

The idea behind Viking’s parachute technique is to use atmospheric drag to slow down the vehicle. The issue is that with very little atmosphere on Mars compared with Earth, you are limited in the amount of drag – and braking – that you can achieve with the parachutes.

Credit: NASA

For smaller landers, that can be enough to allow you to employ other techniques, like using retro rockets, cushioning your lander in an inflatable structure, or the famous MSL skycrane, but for larger masses, you need to do much more to counteract the greater momentum that they have.

We’re also limited in where we can land on Mars. We need all the distance we can get to slow down, so mountains and areas of higher altitude on Mars are currently out of the question as landing sites.

Is the Martian atmosphere really so different from ours?

Yes. If you think of the atmosphere of Mars as being like water, Earth’s atmosphere is more like PVA glue – it’s much thicker in terms of its viscosity. Not only that, but the thickness in terms of how high it reaches above the planet, is much less than that of Earth’s atmosphere too. Imagine you’re on a diving board hoping for a soft landing – it’s the difference between jumping into an inch of water, or a whole pool of glue. I know which I’d choose.

Since there is hardly any atmosphere on Mars, it makes it not only hard for landing, but also means that there isn’t the same protection from radiation on Mars that we get from Earth’s atmosphere. That’s why radiation shielding and underground habitats are being considered.

So what can we do?

That’s the question that scientists and engineers at NASA are trying to answer at the moment. The Jet Propulsion Lab (JPL) is respected as a centre for excellence for entry, descent and landing (EDL) and they are leading a cross-agency experiment to test new solutions to the problem. They’ve recently conducted the second test of the low density supersonic decelerator project – LDSD.

Wait – I heard about that – the thing that looks like a flying-saucer?

That’s the one! Actually there are two parts to LDSD. The “flying saucer” that you’re talking about is their test vehicle, which includes a supersonic inflatable aerodynamic decelerator, or SIAD. Then there’s also an enormous supersonic parachute, called a supersonic ring sail.

Credit: NASA

Supersonic inflatables? Are you making this up?

No! Inflatable structures are NASA’s way of “packing light”. Basically around the rim of the spacecraft they have added an inflatable ring that increases the diameter of the spacecraft. The larger surface area means it creates a larger drag, thus slowing the vehicle down more effectively. On the journey to Mars this would be packaged up inside the craft and it can then be deployed to help slow it down.

SIAD slows the craft down from around four times the speed of sound (Mach 4) to around two-and-a-half times the speed of sound (Mach 2.5).

But that’s still going faster than Concorde?

Yes, but it is hoped that a special supersonic parachute – at 30.5m diameter, the largest ever! – will slow the vehicle down to below the speed of sound (Mach 1).

You said they’re testing it – you mean they sent it to Mars?

Artist’s concept of LDSD Credit: NASA JPL/Caltech

Sending things to Mars without testing them on Earth is not only risky, and extremely costly, but due to the positioning of the planets, we only get a launch window every couple of years. The LDSD team realised that the upper reaches of Earth’s atmosphere – the stratosphere – has similar properties to the atmosphere of Mars.

By filling a gigantic (as in, could fill an American football stadium gigantic) balloon with helium, they were able to lift the test craft up to 120,00ft (36.5Km). They then stabilised it, released it from the balloon and used a rocket engine to boost it right up to the edge of the stratosphere – 180,000ft (55Km) above Earth – that’s around 20Km higher than Felix Baumgartner was when he did his jump from “the edge of space”

Don’t stop now – what happened?

The vehicle was travelling at around Mach 3 and the inflatable element, SIAD, deployed and all indications are it worked perfectly. It is the second time this version of SIAD (SIAD-R) has been tested, and both tests went well.

What about the parachute?

The parachute deployed, but “didn’t perform as expected” according to NASA.

In other words it failed?

That’s not how we like to look at these things. Although the parachute was ripped apart despite being reinforced with Kevlar, and being redesigned since last year’s test when the parachute was shredded, the team have still got some useful data. It’s all about testing, learning and improving for next time – and that’s why it’s good to be able to test things on Earth before sending them thousands of miles away into space.

What happens next?

The team will look at the data and reflect on this test. The next LDSD test is scheduled for summer 2016 – so we’ll have to wait until then to see if they have managed to fix the parachute problem.

But NASA is still planning on going to Mars?

Yep. They want to land humans on an asteroid in 2025 and then humans on Mars in the 2030s. You can find out more on their Journey to Mars pages on the NASA website.

Journalism Q&A by .

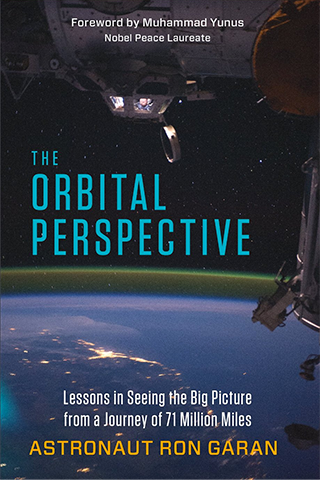

Astronaut Ron Garan. Image Courtesy of NASA

Genial astronaut Ron Garan reminds us to put away our cynicism and rekindle the “anything is possible” attitude we had as bright young dreamers before the realities of everyday adult life came to bear…

In his new book, The Orbital Perspective: Lessons in Seeing the Big Picture from a Journey of 71 Million Miles, Ron Garan draws not only on his time in space – from which the book, and the central premise take their name – but on all the partnerships, and international collaborations that were needed to get him there. He uses the International Space Station (ISS), an enormous feat of engineering and international bridge building, as an example of what can be achieved if we all pull together in the same direction – and wonders what could be achieved to alleviate the imbalances and suffering at ground level if we could capture the same spirit of collaboration and focus it on these issues.

As a huge fan of human spaceflight, I couldn’t help but get goosebumps reading the sections about his mission to the ISS, especially as he describes his first launch on space shuttle Discovery. Having seen (and felt) shuttle launches in person, I am always gripped by these personal accounts of launching into space, so I enjoyed living vicariously through his words as I myself was jostled about on the tube to work.

As a huge fan of human spaceflight, I couldn’t help but get goosebumps reading the sections about his mission to the ISS, especially as he describes his first launch on space shuttle Discovery. Having seen (and felt) shuttle launches in person, I am always gripped by these personal accounts of launching into space, so I enjoyed living vicariously through his words as I myself was jostled about on the tube to work.

These accounts of his time in space are not the main focus of the book, but rather they help in bringing you along on his journey of discovery that has led to this current goal of connecting people, organisations, nations, and businesses to share experiences and knowledge and ultimately, to help change the world for the better.

While numerous astronauts have spoken of the wonder of seeing the Earth from above, with some speaking about the way this has profoundly changed their outlook (the ‘overview effect’), Garan is keen to point out that the orbital perspective is about more than just seeing the Earth from above and contemplating it differently – it requires action. He’s also quick to reassure you that you don’t have to have experienced being in orbit to understand – or to take – an orbital perspective (though I’d be up there in a shot anyway, given half the chance).

Garan’s orbital perspective is all about realising that we are all interconnected and sharing a ride through the universe together on spaceship Earth – our Fragile Oasis. Realising that (and I quote The Hitchhiker’s Guide To The Galaxy here) “you might think it’s a long way down the road to the chemist, but that’s peanuts to space”.

We’re all in this together – if you can step back far enough to see the picture in global, planetary terms, rather than getting lost in teams, groups, cliques, nationalities and the like. It makes perfect sense when you look at it that way (though in the midst of an election campaign things never seem quite so clear!).

I’ve certainly heard astronauts say “you can’t see any borders when you’re in space”, which has always been quite a wonderful, comforting thought. I was quite shocked then, to read that while taking some photographs, Garan had actually been able to pick out the marking of the border between India and Pakistan.

Illuminated human made border between India and Pakistan – Ron Garan/NASA

“Seeing that border from space, a true barrier to collaboration, had a huge effect on me” he writes, then describing the “sobering contradiction between the staggering beauty of our planet and the unfortunate realities of life on our planet for many of its inhabitants”. It was this moment that led him to the idea of the orbital perspective.

Garan describes the orbital perspective as the call to action that comes from the overview effect – that change in perception that astronauts described after having looked back at the world from the unique viewpoint of space.

“The key”, he says, “is ‘we’”. Nothing is impossible if we can connect the right people, use the bigger picture to help us overcome our cultural and political differences, and work together to solve the world’s greatest problems.

As a born dreamer, a person that challenges the notion of “impossible” (until it comes to the laws of physics), and someone who takes pride in making things happen, I find myself quite intoxicated by this idea. It’s exciting, it’s positive, it’s people working together to make things better. I love it.

Before we get too carried away, Garan reminds us that while the big picture is all very well, you have also got to consider the “worms-eye view”. In standing back to ensure that you see the whole picture, you are undoubtedly missing the intricate details that create it. Without an understanding of the realities of life on the ground, no matter how perfect your solutions might seem from afar, they could fail at the first hurdle. You need to ensure that you explore both extremes of perspective in order to identify schemes that can work in the long term, and also improve the everyday lives of people.

It’s not a simple task, but Garan returns to the way that the ISS project was realised and created, using the essential skills and contributions (both physical and intellectual) from two previously warring nations.

It’s not a simple task, but Garan returns to the way that the ISS project was realised and created, using the essential skills and contributions (both physical and intellectual) from two previously warring nations.

He pays tribute to all those who went the extra mile, working to build up the strong –at times vital – personal relationships that allowed Russia and the United States to come together and work as indispensable partners in space. The message is clear – if humanity can put aside its differences and create an orbital space station – continuously inhabited by multinational crews for over a decade – why can’t we achieve other great things?

Garan also turns to the example of nations, companies and intellectuals coming together to help free the Chilean miners in 2010. It was a do or die situation and those in charge were smart (and humble) enough to know that this wasn’t something that they could do alone. With contributions and coordination, including utilising NASA’s experience and knowledge of living in confined spaces, what could have been a deadly national disaster became an incredible international rescue story, touching people around the globe.

There’s no doubting that great things can be achieved, and that we could all benefit from a more global way of thinking, but how do we make that happen?

Garan talks about schemes that are already bringing people together, hackdays like NASA’s International Space Apps Challenge and organisations like Engineers Without Borders, his enthusiasm is infectious. He also talks about the need to ensure that we don’t just double up our efforts, but rather coordinate and work together to build even more impactful solutions.

Garan talks about schemes that are already bringing people together, hackdays like NASA’s International Space Apps Challenge and organisations like Engineers Without Borders, his enthusiasm is infectious. He also talks about the need to ensure that we don’t just double up our efforts, but rather coordinate and work together to build even more impactful solutions.

This is an inspiring book that I would encourage everyone to read – I’ve already passed it on to the director of the charitable foundation that I work for – and there are definite lessons to be taken from it. Not only in the big picture sense of making the world a better place, but there are many everyday lessons that could make the average workplace better. Issues that he identifies that particularly affect non-profits – quick turnover of younger staff members who come to do something good and experience new places for a while, before being enticed away with higher paying careers – can have an effect in many places.

The communication channels between vibrant directors and leaders with a strong vision and those on the bottom rungs of organisation, who may be full of new ideas and perspectives, need to flow. All too often there can be a sticking point in the hierarchy and bureaucracy of managers in-between.

Garan also opens our eyes to headline-grabbing charitable projects that may not have the required infrastructure behind them to ensure that the initial benefit lasts. A striking example Garan explores is why charities may prefer to install new water-pumps, rather than spend money ensuring that existing ones can be restored and maintained for many years. It’s all about how we measure success, and a system of funding that may be hostage to the need for headlines in order to raise new funds.

With the ever-increasing disparities in wealth around the globe it is obvious that the system is broken. Garan’s book reminds me of the optimism and hope that I had as a child, and that I still have, despite various battle scars from life.

Garan makes us believe in the potential to make a difference, together, but I guess my biggest question, having read the book, is “what can I do?” – I’m not an engineer, or a coder, but I do have enthusiasm and ideas. I’m still working on how I can be useful, so if you have the answer, let me know!

The book is (not wanting to sound dismissive) idealistic, but importantly he ensures there is substance behind the idealism. Whether Garan’s orbital perspective has the strength to help fix our global problems remains to be seen, but it’s certainly a step in the right direction and I’ve got every confidence in him to inspire people to help make a difference - I can vouch for his personal charisma and charm.

Viewers of the X-Files may recall a poster in Fox Mulder’s office, which sums up my feelings about the orbital perspective and it’s energetic optimism about our ability to work together and change the world: “I want to believe”

Review by .

(Hastily written on tube journeys – forgive typos)

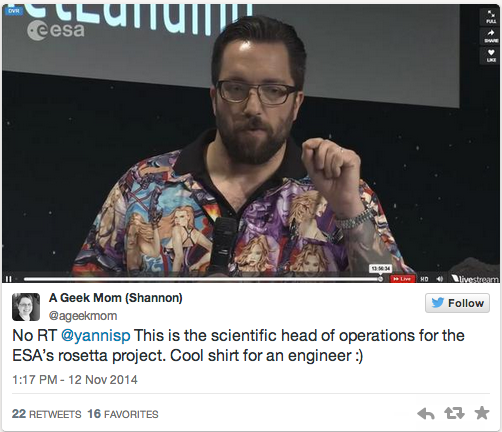

This morning I’m full of conflicting emotions. So excited -so excited – that ESA managed to pull off the incredible feat of landing Philae on comet 67P, but also sad. I’m sad, truly disappointed, upset about that shirt.

The shirt I’m referring to of course, is that worn by Rosetta lead project scientist Matt Taylor during the coverage of this historic landing. He took it off at some point, either waking up to the fact it was hugely offensive to many people, or because he was advised to by someone in the press team, but the damage was already done.

Following the landing on Twitter, with friends all round the world, I didn’t want to be distracted from the mission. When I first saw tweets and small auto-loaded images that mentioned the shirt, I thought they were referring to it’s garish colours. It was certainly um, “eye-catching”. But then I looked closer, and saw it was covered in images of semi-naked women. Er, what? My first thought was that it should never have been made, let alone bought, let alone worn – never mind the fact the eyes of the world were on this coverage.

At work, and only able to sneak glimpses of the landing coverage via Twitter, I didn’t think too much about it. I sort of figured this was some quirky scientist attempting to have their moment of fame by emulating Curiosity landing’s “Mohawk guy”, wearing something bright so they could be picked out in a crowd.

It was only later that I realised this wasn’t just anyone, this was one of the lead scientists of the mission – one of “the faces and voices” of the mission. Ah, this is the guy who had the landing tattooed on his leg, before it happened, so confident (or hopeful) that it would happen. I thought that was cool. It showed real passion and dedication and love of his work. Showing that scientists aren’t just the stereotype of old, serious, white male in a lab coat.

So what went wrong? How could this happen?

I’m going to give Matt Taylor the benefit of the doubt. Let’s say he just didn’t think about his choice of shirt in that way and didn’t realise that it might upset people. Let’s just imagine he wanted something bright and “non-lab coat”. Let’s imagine that he wanted to do something positive by wearing something bright and showing that science can be fun.

My question is how could anyone at ESA have allowed him to wear it on screen? I know they were all busy, so busy, I know they had other things on their mind, I know you might think “get over it Kate, it’s just a shirt”, but this has really bothered me. Here we are, making history, making great leaps forward, and yet the historical record will show just how backward we were. Here was a chance, with the whole world watching, to show a new generation of potential scientists that this stuff is cool, it’s exciting, and it’s for them – and yet with one bad clothing choice we’ve potentially alienated half the audience.

I’m cross. I’ve campaigned previously to keep sexism out of space. These things might seem small, but the effect is toxic. I’m sad. So sad, that at this great moment, this never-to-be-repeated galactic first, that no-one stepped in and said “mate, what are you thinking, take that off!”.

I’m sad that no member of the press and PR team, no member of management, no team member or journalist said “take that off before you represent the leading edge of human achievement”.

There was some uproar on Twitter, but actually this wasn’t just a “Twitterstorm” for the sake of it – in fact I was really impressed at the way Erin Ryan gave it a more positive angle by highlighting some of the female scientists and engineers that were part of the team, noting for each of them that #shedeservesbetter.

The shirt disappeared later in the day, but by then press interviews had been done, and as I watched the BBC Ten o’clock News, there it was again. That shirt.

It might not have been quite such a big problem if it was confined to the live coverage on the ESA stream – lots of people were watching, yes, and lots of them could feel disappointed by it, sure, but the fact it made it into the mainstream media coverage, that’s a really big problem. Now we have many thousands of people, the audiences that space and science might not always reach, exactly the sort of people we need to excite – and this is the glimpse they get of the space family.

Not good enough.

I’m sad that the journalists interviewing him didn’t stop and suggest he take the shirt off, point out that it might detract from his message about great science. I’m just so sad that this could happen.

Since I started writing this post I know there have been several others posting on the topic, I saw Matt Taylor on the front of the Evening Standard yesterday with an interview from his family saying that he is super smart but can lack common sense (I didn’t see a reference to the shirt) and I’ve even seen horrible abuse aimed at people on Twitter who (rightly) called him out on it.

I’ve been asked whether my love of space exploration trumps the issue of objectifying women. My answer is a clear no. They are different things. Yes, I’m totally thrilled that we landed on a comet and we did that no matter what people were wearing, but do I think the coverage has been marred by “shirtgate”? Yes. Without a doubt. Here was the most fantastic opportunity to show that space is for everyone, and yet that stupid shirt sent out an entirely different message, consciously or not.

In fact maybe that is the issue here, that we’re so used to this sort of thing that it doesn’t register with people as being sexist or damaging. Well we shouldn’t be, and we certainly shouldn’t be raising the next generation to just accept it either.

I’m sad that I’m writing this post and not just raving about the super coolness of landing on a comet, but you know I think that’s amazing, and I know that story is being told elsewhere, so I think it’s important that I add my voice to the others, in expressing my disappointment at this – at best a missed opportunity, at worst a damaging step backwards.

I know people working in media at ESA. They are good people. They work hard. They probably realise that this is an issue too. This is not about blaming anyone, but making the point that this wasn’t okay. We simultaneously took one giant leap for humankind, and one giant leap backwards.

So what now? I would like to hear from Matt Taylor – to find out what he really thinks. An apology and a strong statement that gives the women on the Rosetta team the respect that they deserve. As for ESA? A concerted effort to highlight all the great and inclusive things that they do – all the brilliant women that made this mission possible – and all the opportunities for the next generation of female engineers and scientists to be part of this incredible international partnership.

UPDATE:

Matt Taylor made a heartfelt apology for the offence he caused during an ESA hangout today where scientists were updating us about the status of Philae. It was genuine and I thank him for it. I still question why those around him didn’t do something which could have avoided this situation, but I’m confident that a lesson has been learnt and people will be more careful in future. It is important that we learn from mistakes, and acknowledging it was a mistake is a good first step. Thank you Matt. Now let’s get back to rooting for Philae and hoping there’s enough power for the next communication window later tonight.

I do moderate comments on my blog, to stop spam, but I’ve approved all the comments that have come in today, precisely because they illustrate some of the issues that we face. It’s not about men vs women, it’s about the level of vitriol in comments on what I had hoped was quite a balanced post. It’s like people haven’t read what I actually said, or just prefer to attack rather than think about whether there might really be a problem. Perhaps it’s easier to attack rather than calmly engage, and therein lies a problem. It shows there is still work to be done, and although I don’t expect my voice alone will make a difference, I hope it will help other realise that it is okay to speak out about things that matter to them. It’s the only way things will ever change.

Opinion by .

Today is a day we make history. After a ten year journey to comet 67P Churyumov-Grasimenko, the Rosetta spacecraft said goodbye to its washing machine-sized lander Philae, which is now on its way to attempt to land on the odd-shaped comet.

This is something that has never been done before – never even been attempted before. It is groundbreaking, exciting stuff.

While it’s being referred to as a comet “landing” – and I’ve even heard people describe Philae “kissing” the surface of 67P as it drops gently down on the surface at a speed of 1m/s – it’s a bit more dramatic than that, as Mark Bentley once explained to me.:

The legs of the lander have shock absorbers to minimise the risk of it bouncing back off the comet into space due to the low gravity on the comet. The Philae lander is then going to have to use hold-down thrusters and harpoon the comet to anchor it down. (I hope no-one tries kissing me like that!)

Will it succeed? We don’t know.

What we do know is that in getting this far, past so many difficult hurdles, the Rosetta mission has already been a triumph. The team has successfully awoken a spaceship that’s been hibernating for years, manoeuvred it to orbit a comet, and collected incredible images of the surface.

The animations of Rosetta and Philae’s incredible journey have brought the mission to life for thousands of people and at 5am this morning, over 30,000 people were tuned in to a live stream showing nothing more than a virtually empty control room.

People are excited about this, and rightly so – it’s a great achievement already. Let’s hope we witness a successful landing this afternoon, but whatever happens, we mustn’t forget that ESA is making history, and we’re are witnessing it unfold in real time. Now that is exciting.

Follow #CometLanding on Twitter to be part of the global community watching this piece of history. @ESA_Rosetta, @Philae2014 and @ESAoperations will bring you the latest news on Twitter throughout the day.

Events by .