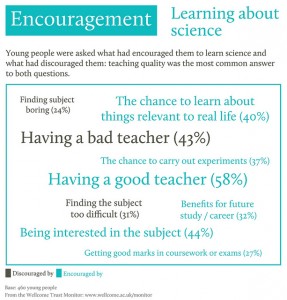

Mars true-color globe showing Terra Meridiani.

Credits: NASA/Greg Shirah

It’s been an exciting 24 hours for the online (and indeed offline) space community – first there was the “Super Blood Moon”, where a lunar eclipse allowed the Moon take on an eerie deep red colour in the early hours of Monday morning, and then NASA revealed what its much-anticipated big announcement trailed as “Mars Mystery Solved” was all about.

“Mars is not the dry, arid planet that we thought of in the past” said Dr Jim Green, Director of Planetary Science at NASA at a media event on Monday afternoon. “Today we are going to announce that in certain circumstances, liquid water has been found on Mars.”

Cue much excitement and many bold headlines, but let’s just take a breath and find out what’s really going on…

So, water on Mars, but that’s old news isn’t it?

Well, yes and no. In 2008, NASA’s Phoenix Mars Lander confirmed the presence of water ice near the surface of Mars, but it’s liquid water that people are especially interested in, as this is considered to be a key to life.

Hasn’t Mars Curiosity found liquid water on Mars?

In 2013, Mars Curiosity rover’s SAM (Sample Analysis at Mars) instrument found that a sample of Martian soil it had scooped up and analysed was 2% water. While not liquid, it was noted as being a relatively high percentage of water.

In April this year (2015), a paper was published that suggested there might be (transient) liquid water below the surface of Mars at Gale crater, according to readings from the Mars Science Laboratory.

So what’s new then?

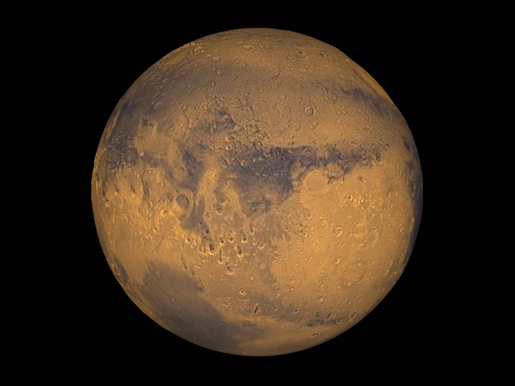

For years spacecraft orbiting Mars have sent back images showing valleys, streaks, and gullies on Mars – they all looked like water was causing them, but there was no proof. Around four years ago scientists discovered features that they have named “recurring slope linnea”, which change with the seasons and temperature. These recurring slope linnea (RSL) – basically large streaks like you might expect to see if water was running down a mountain say – can be hundreds of metres long.

Dark, Recurring Streaks on Walls of Garni Crater. Image Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech/Univ. of Arizona

These “streaks”, pointed to water being the culprit, but “there had been no evidence of water” says Dr Michael Meyer, lead scientist for NASA’s Mars Exploration Program – who pauses for dramatic effect – “..until now”.

An instrument called CRISM (Compact Reconnaissance Imaging Spectrometer for Mars), on the Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter, has been used to analyse the chemistry of the streaks when they appear, and the results of this analysis are what is causing the current excitement.

There were two ways the scientists could confirm that the RSL are formed by liquid water. The first would be to use the spectrometer to detect liquid water absorptions on the surface, and the second would involve the detection of hydrated salts precipitated from that water.

The results published yesterday show the presence of hydrated perchlorate salts in the RSL regions, thus indicating the presence of water – though even when liquid it would be more of a salty mix than something you’d get from the tap!

Where is the water coming from?

We know that Mars has undergone some huge changes in its lifetime. Around three billion years ago it is believed that perhaps as much as two-thirds of the northern hemisphere of the planet was ocean, but Mars suffered a major climate change event and lost its surface water. The rovers that we have sent to Mars are finding a lot more humidity in the air than expected, and the soils are moist and hydrated.

But how do we get from water in the atmosphere, to flowing water?

The preferred theory revolves around the idea of “deliquescence” (yeah, I had to look that one up too). What this means is that the perchlorate salts, which are found on Mars, like to absorb water – so much water in fact that they can at certain times (e.g. when it’s warm enough) become a liquid solution, which trickles down crater walls and other slopes creating the RSL we observe. Perchlorate salts lower the freezing temperature of water by the way.

Other ideas that have been put forth are that the water could come from surface or sub-surface ice melting, or local aquifers. It could be that there are different mechanisms at different locations around Mars.

So now we’ve found water, we’ll find life soon, right?

We often hear the mantra “follow the water”, and so of course finding liquid water is exciting, but as with most science, it’s usually a bit more complex than “found water, will find life”. I turned to Mars expert and NASA astrobiologist Dr Chris McKay to gauge how excited we should be – after all it was his passion for this stuff that got me involved in space in the first place. If this research was as big a deal as the newspapers would have us believe, he’d definitely be excited…

We often hear the mantra “follow the water”, and so of course finding liquid water is exciting, but as with most science, it’s usually a bit more complex than “found water, will find life”. I turned to Mars expert and NASA astrobiologist Dr Chris McKay to gauge how excited we should be – after all it was his passion for this stuff that got me involved in space in the first place. If this research was as big a deal as the newspapers would have us believe, he’d definitely be excited…

“All life on Earth needs liquid water to grow or reproduce. Life can be dormant in the dry state” he says. “Brines of sodium chloride (normal salt) are suitable for life even at complete saturation of that salt at -20ºC” – that means life can survive in really salty conditions, and studying extremophiles (organisms that can live in extreme conditions) as Dr McKay does, is a good way of understanding the limits of life.

He goes on: “However there are brines on Earth that are too salty for life. The most famous is Don Juan Pond in Antarctica. This is the saltiest liquid water on Earth and is composed of saturated calcium chloride. Nothing can live in the brine of Don Juan Pond.”

“The “liquid water” discovered on Mars is brine, and is a saturated solution of a salt known as perchlorate. This brine is even saltier than the calcium chloride brine in Don Juan Pond.”

Ah, this doesn’t sound good. It’s not time to get the “Welcome Martians” party banners out then?

Back to Dr McKay: “Such a brine is not suitable for life and is of no interest for biology. The result is of interest only geologically.”

Hmm. So basically, while this is fascinating research all the same, the “water” found on Mars is so salty it probably couldn’t sustain life (as we know it) – and even the Nature Geosciences paper says that: “If RSL are indeed formed as a result of deliquescence of perchlorate salts, they might provide transiently wet conditions near surface on Mars, although the water activity in perchlorate solutions may be too low to support known terrestrial life”.

I guess we best keep on searching then, and take those headlines with a pinch of (perchlorate) salt, eh?

Journalism Q&A by .

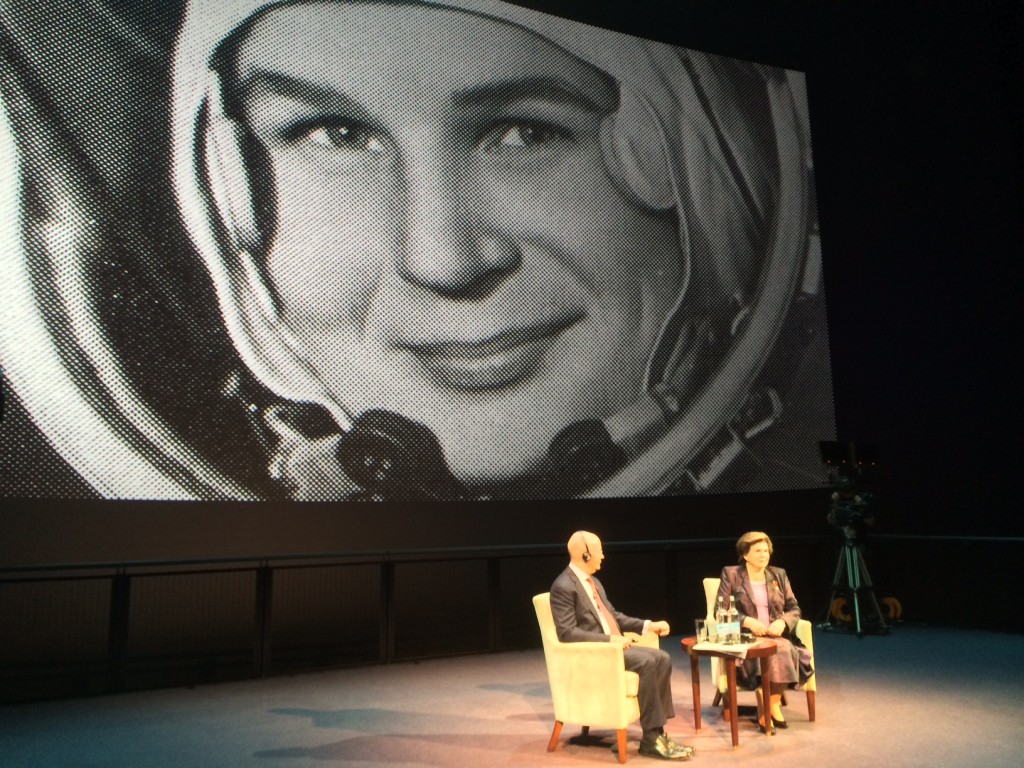

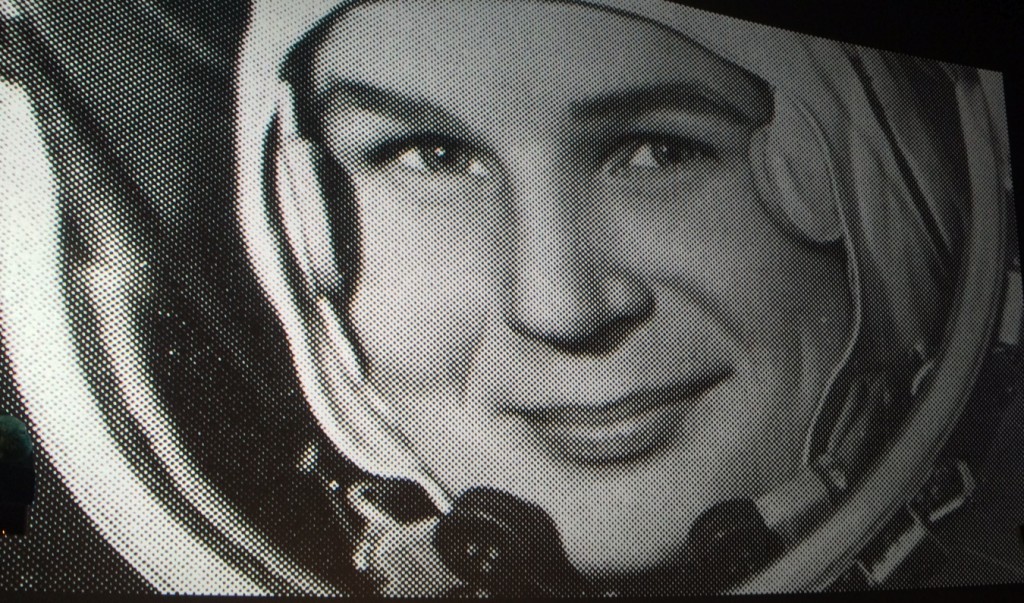

Cosmonaut Valentina Tereshkova – first woman in space, and only female to have done a solo spaceflight – was always going to be on my list of heroes. So as I walk into the large IMAX auditorium at the Science Museum and take a seat for a special Q&A session with her, I can barely sit still. Projected on the screen is a huge black and white photo of her in her space helmet. It’s a wonderful image, and I hear the people in the row behind me echoing that thought.

She enters, with Science Museum Director Ian Blatchford, and I pop on the headphones connected to a small device that will supply a translation of her words. It’s safe to say I’m excited about what I’m about to hear. And I’m not disappointed. In fact, I’m mesmorised. Valentina Tereshkova is cool.

She’s funny, occasionally self-deprecating, and she’s also kinda badass (if that’s not too crude a word to use about a living legend). Here she is sharing her story, right in front of me. I did my best to take notes so that I could share it with you.

“Before life as a cosmonaut, what did you want to be?” asks Blatchford. “Is it true you wanted to be a train driver?”

“Every child thinks about what they would like to be”, she says. “I was from the war generation, we dreamt about peace – we wished for a time we didn’t have to see our parents cry”. Tereshkova explains that when she was young, she lived quite close to a train station, and would watch the trains go by on the way to Moscow and other places. “They must be so lucky” she thought, referring to the fact they got to see so much. Her mother was sceptical about her following this line of career ambition. “Maybe something different?” she suggested.

After Yuri Gagarin flew to space, there was no boy or girl who didn’t want to be a cosmonaut she says. She joined a sky-diving club and all the sky-divers and parachutists thought that they should be the ones to become cosmonauts. On the other hand, all the pilots were convinced that they should be the first cosmonauts.

Tereshkova was invited to Moscow, where she underwent rigorous check-ups and tests, before being recruited as a potential cosmonaut. It was all highly confidential. She said goodbye to her mother, and made up a story about participating in a parachuting tournament.

When the newly selected cosmonaut candidates passed Gagarin in the corridor, “we looked at him as though he was God” she says. “We tried to touch his sleeve” and he asked them “why are you trying to stroke me?!” They explained their story and he showed interest in them.

In the 1960s there had been years of confrontation between the US and the USSR, and there was a lot of competition with regard to space. Tereshkova said that they knew the US was also training women, “but the USSR outdid America again”. On 16th June, 1963, she went up into space.

They had just two years to train – “it was rather difficult, a lot of work” she says, “and we had very limited time”. “We had to say bye to ‘living’ on Earth – we were at Star City, 40Km from Moscow – there were no weekends, and no entertainment” she recalls.

Valentina Tereshkova’s capsule, Vostok-6. Credit: Kate Arkless Gray

Tereshkova was due to fly the week earlier than she did, but there was a lot of solar activity and so the flights were shifted to a later date due to the additional radiation risk. Ahead of her launch, on 14th June, Valery Bykovsky launched on Vostok 5. As with Vostok 3 and 4, the two craft came close to one another and established radio contact in space. Tereshokova’s Vostok 6 launching on 16th June, and when they finally made contact she said “Valery, let’s show that we are okay and we are enjoying the view, let’s sing a song”. “I am not a singing bird” came Bykovsky’s response, “you sing, I will be listening”.

Tereshkova says that she and Bykovsky are still in touch to this day, and when she sees him, she reminds him that he wouldn’t sing with her, “I still don’t want to sing with you!” comes his response, but the ways she tells it, it sounds as though it’s all in good humour.

Tereshkova is asked about the emotional side of spaceflight and there’s an immediate sparkle in her eye. “I love the non-technical speak” she says. “When I was accelerating and the rocket was rising from the Earth I was shouting ‘skies – take off your hat! We’re coming’”. Gagarin asked her “have you forgotten the sailors?” For sailors a woman was a jinx to a ship, and he was saying ‘don’t jinx your flight’, she explains. He laughed a lot about this afterwards –asking “where’s the hat?”

When Tereshkova flew over Yaroslavl Oblast, where she was from, she felt emotional knowing that her mother was there, but quickly realised that she was so busy with the flight that there was “little time for emotion”.

At the time that she flew, her mother, Elena Tereshkova, had no idea that her daughter was a cosmonaut (her father, Vladimir Tereshkov, was killed in Finland while Valentina was just two years old). When one of the neighbours came round shouting “Elena! Your daughter is in space!” her mother calmly replied “you must be dreaming, she is skydiving”.

In fact Tereshkova had written ten letters before her trip, and asked for them to be sent on her behalf. Some sources claim that her mother had been reading one of Tereshkova’s letters about the sky-diving tournament when she received the news from her neighbour. The family didn’t own a television at the time, so it was only when the neighbour brought Elena round to see it for herself on television that she found out.

RIA Novosti archive, image #612748 / Alexander Mokletsov / CC-BY-SA 3.0

All cosmonauts were made to report back after their flight, and when Tereshkova began speaking, in front of Soviet Leader Nikita Khrushchev, she heard her mother’s voice: “Aha! She deceived me”. Krushchev apparently also heard this, going up to her mother to say “please forgive her, it’s her first mistake..”

“..but she was skydiving, she had to parachute” he added.

Vostok craft are different from the current Soyuz capsules – rather than land inside the capsule, you had to eject at around 7Km up and parachute down.

Bykovsky landed in Kazakhstan, but with no aerodynamics, “you could land anywhere” says Tereshkova. She ended up landing in a field in the Altai Region. “I had to be different, as a woman” she says with a smile.

When she landed in the fields, with the aid of her parachute, the women in the field came and said “come on, we will feed you”. She wanted to give them something, and so she handed out some of the space food that she had, which got her in some trouble. “I gave some away – we don’t have to tell everyone” she recalls answering when the agency asked her how many tubes of food she had.

Tereshkova was lucky to have landed at all. A mistake was made with the navigation software on Vostok 6, which, had Tereshkova not spotted it in time, would have seen her launched further and further into space with no way back. Thankfully she did notice, and Sergey Korolev (Head of the Soviet Space Agency) and Yuri Gagarin calculated a new landing algorithm, which she inputted, ensuring she did get back.

Tereshkova says that Korolev was known for “scolding us as much as loving us”. He gathered everyone to find the culprit – the person responsible for the mistake, and found them, but Tereshkova helped save him. On her return, Korolev said “My darling seagull, don’t tell anyone. Everything went well”. (“Seagull” – or “chaika” in Russian – was her call-sign).

“I kept mum” says Tereshkova, on the condition they didn’t punish him, but on the 30th anniversary of her flight Evgeny Vasilievich, the engineer in question, chose to come clean about it saying “people need to know the truth”. Tereshkova says she was “horrified” when he did this, as she had promised Korolev never to say anything.

Someone asks Tereshkova whether her flight was seen as a triumph of engineering and science, as well as a personal and national, triumph? “Naturally” she replies. “Having women in space – showing that a woman’s body would act in the same way as a man’s body”, she talks of her ballistic re-entry “9.5G – it is heavy going” she says. “Each flight was a test – a trial, for the body and science” says Tereshkova” she says. “The first flights allowed us to put in our comments and to perfect the craft.”

Tereshkova explains that the cosmonauts of the time didn’t realise the level of “popular love” that they would receive upon their return. When she had her daughter she got many letters telling her that she should give her daughter a “space name”. Instead she honoured her mother and called her daughter Elena. “She’s a doctor – my happiness, my joy” says Tereshkova. She speaks of the children and grandchildren of other cosmonauts and we learn that Alexei Leonov’s daughter “treats her parents well”, which you can tell is important to Tereshkova. “Our space fraternity tries not to betray each other” she says, “we stay loyal”.

Sergey Korolev had the idea to fly an all female team recalls Tereshkova. She indicates that they had been training and preparing for such a flight around 1965, but in 1966 he died. “It was a huge tragedy to lose such a designer, scientist, visionary” she says. When people looked at his plans “there was pure chauvinism” she says, “we were pushed aside – it was unthinkable to send women”. She tried to let it go – “we were bitter and sad, but still wanted to continue – there was a new craft, Soyuz”.

But with the tragedy of Vladimir Komorov’s flight – Soyuz 1, and then Soyuz 11 ending in disaster, with the capsule depressurising during re-entry preparations, killing all three crew members, the female cosmonauts were told “we won’t be risking your lives”. They were dismissed. “This is our sad story” says Tereshkova.

But with the tragedy of Vladimir Komorov’s flight – Soyuz 1, and then Soyuz 11 ending in disaster, with the capsule depressurising during re-entry preparations, killing all three crew members, the female cosmonauts were told “we won’t be risking your lives”. They were dismissed. “This is our sad story” says Tereshkova.

After Tereshkova’s flight it took 19 years for the Soviets to send another woman into space – Svetlana Savitskaya flew in 1982. (The US put their first female astronaut – Sally Ride – into space a year later – in 1983, 20 years after the Soviets flew Tereshkova.)

During the opening celebrations for the Cosmonauts exhibition, which is currently on at the Science Museum in London, Museum Director Ian Blatchford and Tereshkova made a deal to go in to space together. “Ian will sing Russian folk songs in space” she says, “and she will sing English ones” says Blatchford.

“Shall we start now?” Tereshkova asks enthusiastically. “Nyet!” replies Blatchford, firmly. “So, you can’t trust a man really, can you?” says Tereshkova, raising a laugh from (at least) the female members of the audience.

What of the future? “We desperately need new engines and spacecraft” says Tereshkova. Getting to Mars “could become a reality sooner if scientists from other countries all work together – only then could we do it sooner” she says.

“It was my dream to go to Mars” says Tereshkova “I’m quite happy to go there one way, to stay there”.

“It is such a shame that time flies.”

Amazing Encounters by .

Credit: NASA

Sergey Krikalev is a softly spoken, humble gentleman. Meeting him, you wouldn’t guess he’s been awarded the highest accolades of both the Soviet Union and Russia – he’s a hero of both. With six spaceflights and eight spacewalks under his belt, he was, until very recently, the holder of the record for most time spent in space – over 803 days…. That’s more than two years spent orbiting the planet. But “I didn’t do it for the record” he says.

As if that’s not enough, he was the first Russian to fly on NASA’s space shuttle, was part of ISS Expedition 1 – the first construction mission, and is also sometimes referred to as “the last Soviet” on the basis he left the USSR for space, and by the time he came back to Earth, it no longer existed!

As if that’s not enough, he was the first Russian to fly on NASA’s space shuttle, was part of ISS Expedition 1 – the first construction mission, and is also sometimes referred to as “the last Soviet” on the basis he left the USSR for space, and by the time he came back to Earth, it no longer existed!

I first met Sergey at a conference about the International Space Station, held in Berlin in 2012. It was a fascinating event, with representatives from the major ISS partners discussing the benefits of the space station, what an incredible feat of engineering and cooperation it is, and sharing some of the science that had come from it.

My friend, cosmonaut Anton Shkaplerov, had just returned to Earth from a six month stay aboard the ISS, his first trip to space. I was keen to hear how he was doing, and after a presentation Sergey gave, I went up to ask him, as head of the cosmonaut office, if Anton was okay. He was fine I heard, and I made way or all the autograph hunters wishing for Sergey to sign their programmes.

It was only really then that I realised that I’d spoken to quite the legend in spaceflight (or indeed any) terms, and I wished that I’d been able to talk to him some more.

A little later during the conference, at a dinner at a local museum, I found myself walking round the collection of communication instruments and old telephones with Sergey. He was keen to learn about things, to take everything in, and he enjoyed walking and talking. I learned about his past as an acrobatic pilot – a national champion no less – and was keen to hear more about his time in space.

He’s humble, fascinating, incredibly smart, and there is a sparkle in those blue-grey eyes as he makes a little joke here and there. I ask him whether they ever had vodka in space. “Vodka in space is bad” he tells me, and I’m not sure if he’s reprimanding me for suggesting that they might be daft enough to risk mixing the highly technical environment of a space station with alcohol. He follows up by saying “but Cognac…”- he gives me a smile and says no more.

Credit: NASA

Like many Russians, Sergey usually looks serious, concentrated. I look through images of him in space, and even there, as he floats around and enjoys the view of Earth, there’s only ever the hint of a smile – except one picture, where he’s dressed in an orange ACES suit, ahead of his space shuttle mission I suspect, grinning widely. I ask him why that is, why he doesn’t smile more, and he tells me that Russians smile when there is a good reason to smile.

It’s been three years since I last saw Sergey – his visa for the International Astronautical Conference in Toronto last year didn’t come through in time – so I’m pleased to see him in London at the opening of the new Cosmonauts exhibition at the Science Museum. He sees me, and smiles. I’m happy he still remembers me. What follows is the best tour of an exhibition charting the birth of the space age that you could wish for, until he’s whisked away for a VIP dinner by some important looking Russians (who I later find out are the Head and Deputy of the Russian space company Energia).

He points out the Soyuz engine at the entrance, tells me about the sample return mission to the Moon that the Russians carried out even before the US made it there. If you listen to the experts at NASA, they will tell you that all the Moon rock on Earth belongs to NASA – they are the only ones who brought it back. Perhaps that is correct, but we shouldn’t overlook the fact that the Russians also managed to bring back a sample, I’m guessing it’s a small amount of “regolith” or Moon dust – so technically not Moon “rock”. They still have it, explains Sergey, and much research has been done.

I discover he has a new role in the Russian space world. He’s working on future missions, looking at possible paths out of low Earth orbit, a post-ISS future.

I ask whether this is an area that the Russians are looking into alone, or as part of a new international collaboration, and he tells me that this is an international endeavour. “What about China?” I ask. There have been discussions, he says, but these haven’t come to much as it sounds as though China wants to collaborate on things that would help them, but not necessarily fit with the overall goals of other partners.

Credit: NASA

What about the ISS itself? While the US side is now considered “complete” – there are no more modules to add – Russia was planning to send a new module back in 2013. This never happened, but is still on the books, slated for launch in 2016. With a new module and docking port, could this make the Russian segment of the space station viable without the US side? (Currently the two halves are reliant on each other for a number of things.) He doesn’t think so, so it seems that when the partners decide to end ISS operations, it really will be the end of the orbital outpost that has hosted people for the past 15 years.

As part of the space station generation, I’m a little sad to think of it crashing back through the atmosphere, with anything that doesn’t burn up, likely laying on the seabed forever more.

But at least he’s thinking of the future, and despite much change in the upper echelons of the Russian space sector, he seems hopeful for the future and enjoying his work. I will be interested to see where it takes him, and of course, the rest of humanity.

Amazing Encounters by .

NASA Administrator Major General Charles Bolden was in London last week to receive an honorary fellowship from the Royal Aeronautical Society. Attending the lecture that accompanied the award I knew to expect inspirational words – eloquently spoken – with glimpses of the personal reasons that NASA’s mission is so important to him. There would be updates on NASA’s diverse missions, hope for the future, and an emphasis on the global importance of international cooperation to enable our journey to Mars.

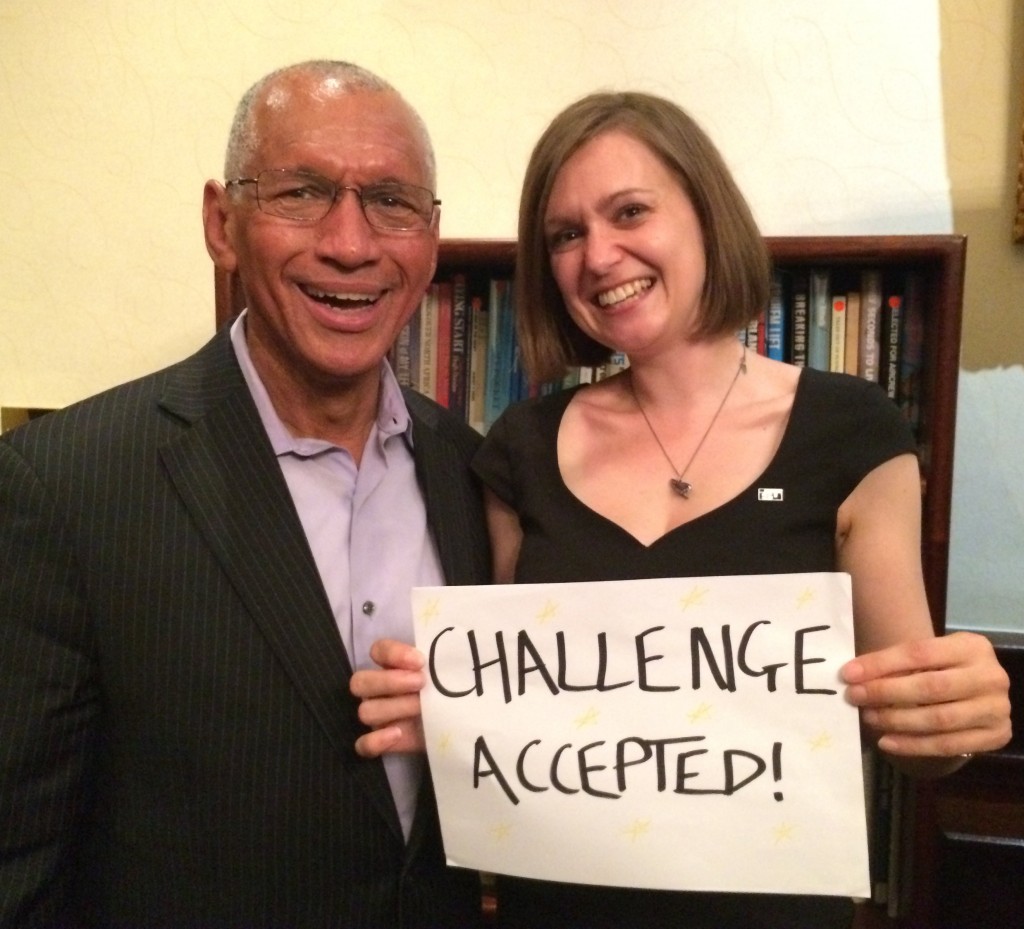

What I did not expect, (and could not even have even dreamed), was that the head of the world’s most famous and successful space agency, would pick me out from the crowd, personally introduce me to the audience as “SpaceKate” and publicly set me a challenge to get more young people involved and engaged with space.

Yet that’s exactly what happened.

“I’ll be checking up” he said as I battled the urge to squeak with excitement and hoped I wasn’t glowing red with humble embarrassment. Internally I welled up with pride.

When the Head of NASA issues you a personal challenge, what do you say?

There’s only one thing you can say of course – “Challenge accepted”.

Rise to the Challenge

Anyone who knows me knows that I like a challenge, so rather than just bask in the glory that Charlie Bolden knows my name, I immediately got thinking about what I could possibly do to rise to the challenge, and repay the great kindness he’s shown me over the years.

I offered to help the Royal Aeronautical Society Space Committee in any way I can, encouraged younger members of the audience that I met at the reception to join UKSEDS and the Space Generation Advisory Council, and am pushing to organise SpaceUp:UK (#2) for later this year. I will continue to talk to any and everyone about space, to blog, appear on Sky News (for as long as they invite me!) and pass on stickers, pins and any other space goodies to people I sense will treasure them. But all those are the sort of things that I would be doing anyway, and a challenge like this deserves something a bit extra.

It’s not just about youth, it’s about diversity…

Looking round the audiences of space-related events at the British Interplanetary Society and even the Royal Aeronautical Society, I can see why Charlie issued to the challenge he did. If we’re going to talk about the future we need to ensure that the people who will help make it happen – and will live it – are included and engaged. But there’s more to it than that for me – it’s not just youth that the industry needs, but diversity too. So how do we become more inclusive?

Not enough female engineers? Perhaps we should tackle the way we describe engineering, ensure that we properly link what is taught in schools with what is taught at university, and most importantly, show how it impacts the real world (not just exam answers!).

Not enough young people at space events? Let’s think about where we advertise them, and consider whether they are truly accessible?

How can we ensure diversity? How can we reach people around the country, from different backgrounds, different cultures? How can we ensure that young voices in the UK are heard both by the community here and on the global stage? How do we connect them with politicians, agencies, budget holders?

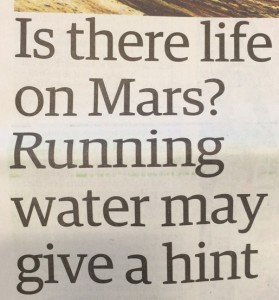

In my mind, education is the key – and while research has shown that good teachers can be the most important things that lead people into science, the converse can also be true. Non-formal learning is another important way of introducing children to science in creative and engaging ways. But what about those families less able to get out to museums or events? How do we reach non-traditional audiences and bring them along on this exciting journey into the future? These are all big questions, and so I need your help…

Build the future you want to see

For decades people have imagined a future where people have personal rocket packs or zip around the place in their jet cars, but that future has never quite happened. If we want to inspire the next generation of space professionals, we have to inspire them early on, and “make it real”. We need to empower them to build the future that they want to see, and show them that science and engineering are key to that future – not just abstract concepts.

The future I want to see is one where your background, class, nationality, gender, etc makes no difference to your chance of being a leading scientist, engineer, astronaut or whatever you want to be.

So how can I achieve that? Well I can’t, not without help – your help – and that’s why I’m asking you to join me to take on Administrator Bolden’s challenge, and help inspire the next generation of space fans. I’ve got a plan…

Give a child a jetpack

Okay, not literally, but give them a boost – open their eyes to what’s possible – perhaps they’ll be the one that makes personalised jetpacks real for all of us!

Don’t underestimate the power of small things to make a difference. For me it was a NASA pin badge, kindly gifted to me by NASA’s Dr Chris McKay. There is always something that you can do – all of you.

Meeting a real person, who worked for real NASA changed my life. It transformed space from something cool that you see in films to something worked on by real people. It sounds daft, but growing up in East London, even doctors and lawyers felt like a different species, let alone people working for space agencies.

The best way to describe the feeling is to say that NASA, space, astronauts etc – they were like Father Christmas; you know they exist, but you’re never going to meet them. I’ve been lucky enough to meet all sorts of amazing people, so I try to share that with as many others as I can, to make it real for them. I like to think of it as my way of paying forward the kindness shown to me – but what can else we do?

If we use our experiences, our skills, our professions, our influence – our passion – we can open up the space profession to young people who might not even realise it’s an option. The more people who realise that the space industry is real, and something to aim for, the better.

How you can help

Image credit: Michael McLean. CC-BY-ND

Are you a scientist, a teacher, an engineer, technologist, or careers advisor? Perhaps you’re a storyteller, space enthusiast, or an explorer? I need you all, and many more, to spread the message that the space industry is open to all, that science and engineering are essential for the future, and that people can help make their dreams reality and take humanity forward.

I’m building a list of resources to help you on your missions – information for teachers, organisations you can join or encourage others to join, competitions, events, and general cool space news that you can share with other people. Encourage others to share them and inspire more young people to get involved, and get your peers to accept this challenge and make a pledge too. If I can get two people to take on the challenge, and they each get two more and so on, we really can make a difference.

With your help we can reach new people, non-traditional audiences, and help develop the next generation of space professionals.

Together we can change the future.

Make your pledge now

Not everything has to be grand gestures remember – so think about what you can do to open doors and ignite a spark of passion, and then do it. Tell people about your work, nurture enthusiasm, share space goodies, give talks in schools, tell you teacher friends about things their schools can get involved with. There are a whole host of different ways you can help.

My pledge is to make SpaceUp:UK happen (again) and to offer to talk my old school and share my experiences to help students see it’s not just the world, but the entire solar system that’s their (proverbial) oyster. I’m making that pledge publicly so that you can hold me to it.

Share your pledge in the comments below – and let’s make things happen. Help me build up a useful list of resources.

If you’re from a traditionally under-represented background and have ideas about how to make things more inclusive please do get in touch and share your ideas.

Let’s see if we can start something together, to get more people interested, engaged, and eventually involved in the space industry and bring them on the journey to Mars.

Space didn’t feel like an option for me when I was young, but meeting someone from NASA made it real for me. Now I’m friends with Charlie Bolden(!!!) so if that’s possible, just think what the next generation of scientists and engineers could achieve.

Are you ready?

Then join me: Take on Charlie’s Challenge and pledge to introduce the wonderful world of exploration, science, and engineering to future members of the space family.

Make your pledge to do something – do it now – and keep us all updated. After all, the Head of NASA will be checking up, so let’s show him what passionate people we have here in the UK (and around the world) and that we can make a difference.

Ad astra my friends! Let’s go!

Follow me on Twitter as @SpaceKate to keep updated with the latest space news (and my mad adventures!)

Amazing Encounters by .